Human Rights in Argentina

2016 Report

1. memory, truth and justice policies 40 years after the coup

2. rights infringements in land occupations and settlements

3. building a regressive agenda around the "narco issue"

4. the intelligence system in democracy: a human rights agenda

5. lethal violence involving the security forces - buenos aires metropolitan area

6. investigation and judicial sanction of torture cases

7. consequences of the sustained increase in incarceration

8. institutional violence against women and "ni una menos"

9. access to justice as a human rights matter

10. freedom of expression: discouraging prospects

CRÉDITOS

investigación, textos y edición

Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales - CELS

diseño gráfico

Mariana Migueles

desarrollo

Clic Multimedia

prologue

0

Gastón Chillier

executive director of CELSI

During its first 100 days in office, the Cambiemos (“Let’s Change”) governing coalition made decisions that had an impact on human rights in Argentina. The measures of greatest consequence include the declaration of a national security emergency, the confusing unveiling of a protocol that seeks to limit social protest, the dismantling of areas of the state that participated in investigating business complicity with crimes against humanity, and the arbitrary and illegitimate detention of a social leader.

memory, truth and justice policies 40 years after the coup

1

Luz Palmás Zaldua, Verónica Torras, Sol Hourcade, Sebastián Blanchard and Tomás Griffa

with the collaboration of Edurne Cárdenas and Gabriela Kletzel. The section on business responsibility is based on the study "Corporate responsibility in crimes against humanity"Argentines flooded the streets on the 40th anniversary of the last military coup to repeat the cry of “Nunca Más.” That same day (March 24, 2016), US President Barack Obama joined President Macri at the Parque de la Memoria memorial site to pay tribute to the dictatorship’s victims – reflecting the broad social consensus forged over decades in Argentina regarding the right to truth and the need to hold to account all of those responsible.

Although Macri has publicly stated that the court cases investigating and prosecuting these crimes against humanity must run their course, some personnel cuts and state office closures carried out under his presidency threaten to weaken the implementation of policies related to memory, truth and justice.

The trials themselves must move forward at a faster pace, due to the advanced age of the accused and some of the victims’ relatives. At the end of last year, 184 judicial cases on crimes against humanity remained in the investigative stage. The investigation and prosecution of civilians responsible for crimes against humanity – particularly businesspeople and judicial and Catholic Church officials – needs stepping up. In March 2016, a businessperson was convicted for the first time of crimes against humanity committed against his company’s workers. But in other similar cases, the judiciary has shown resistance to proceeding.

In November 2015, Argentina’s Congress passed a law creating the Bicameral Commission for Identifying Economic and Financial Complicities during the last dictatorship, which must release a report on its findings. In December, CELS and others released a joint, two-volume study on Corporate Responsibility in Crimes against Humanity, which was presented to the Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes against Humanity to facilitate future investigations. These initiatives are in line with international efforts to hold economic actors responsible for human rights violations.

rights infringements in land occupations and settlements

2

Carlos Píngaro Lefevre, Eduardo Reese, Florencia Brescia, Guadalupe Basualdo, Luna Miguens, Manuel Tufró and Marcela Perelman

The difficulty in accessing decent habitat is at the heart of the country’s biggest social problems. In the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area, informal access to land and housing has increased. Between 2003 and 2015, while private developers and the state built the largest number of housing units on record, land occupations actually rose in response to skyrocketing property prices.

After conducting eight months of field research, we were able to confirm that the informal land and housing market has grown both for rentals and purchases, and it often mirrors the speculative logic of the formal market. However, the people living on occupied lands tend to face dangerous environmental conditions and have limited access to basic services such as health care and education. This precariousness has bred disease, and in some cases caused deaths.

Residents of these communities are also vulnerable to extortion by state and non-state actors. High-profile and violent land evictions, as well as the increased frequency of occupations, show the interrelationship between structural restrictions on access to habitat, the state’s repressive and criminalizing practices, and the illegal businesses (relating to the drugs trade, land dealings or other enterprises) that are carried out with police and/or political connivance. Often the causes of land occupations are ignored and the people involved in them are strongly stigmatized.

Government officials at different levels take a punitive approach, or fail to intervene, or do not have the tools or capacity to improve conditions even when they try. The Law of Fair Access to Habitat (passed in 2012 in Buenos Aires province) has bolstered the state’s ability to actively intervene in the real estate market, but its implementation has been strongly resisted by powerful economic groups and part of the provincial state bureaucracy.

building a regressive agenda around the "narco issue"

3

Manuel Tufró, Victoria Darraidou, Agustina Lloret, Juliana Miranda and Florencia Sotelo

The candidates in the 2015 presidential campaign resorted to a discourse that oversimplifies the problems related to the illegal drugs trade, glosses over state connivance, and directly associates drug trafficking with violence and poverty. The supposed menace of the drug “scourge” is used to justify punitive policies that trample human rights, particularly in poor neighborhoods and among young people.

A month after taking office, Macri (who had declared the drugs trade to be the biggest problem facing Argentina) decreed a national security emergency that identified drug trafficking as a “threat to sovereignty.” It also authorized the shooting down of planes suspected of transporting drugs and considered to be hostile – which is tantamount to ordering the death penalty without trial. This decree could enable the militarization of domestic security, in violation of the broad post-dictatorship consensus that led to the passage of three laws under three different presidential administrations that limited military involvement to matters of national defense.

These moves put Argentina closer to hardliners in the global debate on the “war on drugs” paradigm, which is increasingly being questioned by countries in the region and elsewhere that call for alternatives aimed at reducing violence and public health harms. In fact, in places like Mexico, militarizing the fight against drug trafficking has done little to reduce the trade but has done a great deal to foster human rights violations and stimulate state corruption.

In Argentina, crooked members of the police and security forces have expanded their involvement in illegal dealings to include drug trafficking. Numerous high-ranking police officers have been accused or convicted of collaborating with trafficking networks, and in 2015 alone the list of police and security force members implicated in drug-related crimes was long. This shows that in addition to providing protection to dealers and traffickers, some police officers are directly involved in transporting and selling illegal drugs. But the national security emergency decreed in January makes no provision for reforming or imposing greater oversight of the police.

Despite alarmist statements about the “Mexicanization” or “Colombianization” of Argentina’s drug markets, there is little evidence to support the notion that there has been an overall increase in violence or that trafficking networks have become increasingly sophisticated or large-scale. What can be said is that there are serious violence problems in specific areas of some big cities, multiple examples of state collusion, and there is very little intervention in the illegal market itself. The state has been incapable and/or unwilling to pursue the leaders of trafficking rings and instead has flooded poor neighborhoods with police, incarcerating drug users and small-time dealers on a mass scale.

To address the problems associated with the illegal drugs trade, better data and measurement methods are needed with regard to drug trafficking and crime in general. The security forces and the judiciary must be reformed so they are better able to investigate complex crimes and the illegal networks in which police participate. Internal affairs offices and external audits must also be strengthened. Also, the current drugs law must be revamped, above all to stop criminalizing users (a practice that was declared unconstitutional by the Argentine Supreme Court but that still persists). Finally, a set of medium- and long-term initiatives are needed to focus state resources on prevention and treatment, as well as policies that foster social inclusion.

the intelligence system in democracy: a human rights agenda

4

Paula Litvachky, Ignacio Bollier and Ximena Tordini

with the collaboration of Soledad RibeiroA long-overdue reform of the intelligence services was carried out in 2015 after Alberto Nisman – the special prosecutor investigating the 1994 AMIA Jewish community center bombing that killed 85 people – was found shot to death in his home. His violent death, which has been investigated primarily as a suicide, although no official judicial determination has been made, roiled the Argentine political landscape. It also revealed the promiscuous ties between members of the intelligence services, judicial officials (particularly in the federal judiciary), and politicians.

Over the last 30 years, Argentina’s intelligence services have been used to illegally spy on political or ideological opponents and to manipulate criminal investigations to protect the interests of cronies – be they businesspeople, trade unionists, politicians, lobbyists, lawyers or members of foreign intelligence services. This aberrant focus has weakened their ability to gather intelligence on real potential threats to the country, including attacks by terrorist groups or foreign states, organized crime, or maneuvers aimed at economic destabilization. It has also posed a grave threat to democracy because politicians who initially use these methods for their own gain later find they are hostage to the highly autonomous intelligence services and their extortive practices.

Under last year’s legislative reform, the Intelligence Secretariat was scrapped and replaced with the new Federal Intelligence Agency. Thanks in part to advocacy by CELS, the bill included provisions to eliminate blanket secrecy regarding intelligence activities and administrative information, to exert greater control over spending, and to remove the widely abused wiretapping unit from the intelligence agency. This reform had its limitations, particularly because it did not address the spurious ties with the political and judicial systems, but it did make changes aimed at achieving greater accountability and transparency and professionalizing the workforce.

However, initial moves by the Macri administration indicate that full implementation of this reform is not a priority and that political considerations may be weighing more heavily than institutional or technical ones, for example in the decision to transfer the wiretapping unit from the Attorney General’s Office to the Supreme Court because of the government’s poor relations with the current attorney general. In addition, the person appointed to head the new Federal Intelligence Agency is a close presidential ally with no experience in matters of intelligence.

“Important reforms are still pending along with, above all, a decision by the political system to change the matrix of its ties with the intelligence system. The new administration’s first moves do not indicate that this transformation is on the agenda,” our 2016 Report states.

lethal violence involving the security forces - buenos aires metropolitan area

5

Juliana Miranda and Manuel Tufró

There is little public data in Argentina, as elsewhere, on incidents in which the security forces injure or kill individuals. This makes it difficult to assess the lethality of their actions in order to design public policies that would reduce violence and the illegitimate use of force. In the absence of official figures, since 1996 CELS has kept a database on violent episodes involving security forces and causing injury or death in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area, based on press reports. Although the information may be incomplete, the 20-year-long study allows for trends to be observed.

In 2015, at least 162 people died in violent incidents in which members of security institutions participated: 126 were private individuals, and 36 were the security officers themselves. These figures are similar to those seen between 2009 and 2013, showing there is a core number of deaths that the state has not been able to reduce.

Also in 2015, 67 percent of people who died at the hands of the security forces were killed by off-duty officers. That is the highest percentage since 1996, when CELS began gathering this data. Many of these incidents are informed as robbery attempts against police officers, in which the homicide is purported to occur when off-duty officers defend themselves from an assault.

Between 1996 and 2015, 95 percent of the victims of lethal violence committed by security force members were men. And in the cases where their age was available, 87.5% of these victims were identified as men 35 years or younger. Among the women killed by security force members, 33% of cases involved “private uses of lethal force,” meaning they were not related to officers’ professional duties. These cases are often, though not exclusively, linked to gender violence.

These figures make clear that patterns of police violence and, in some contexts, high levels of police lethality exist and have a grave impact on human rights. The lack of official data makes it very difficult to distinguish between justified uses of lethal force, and executions or instances of illegitimate use. “Knowing when, how and why the police kill must be a goal of any government interested in security, the protection of human rights and the implementation of policies to reduce violence,” our 2016 Report states.

investigation and judicial sanction of torture cases

6

Eva Asprella, Mariano Lanziano, María Dinard and Marina García Acevedo

Through our litigation work, we have identified several strategies for achieving justice for torture victims despite structural deficiencies. First it is worth noting that violent treatment has been the norm for people detained in Buenos Aires province for decades. This is related to weak political oversight of security forces and penitentiary institutions. As a result, the judiciary has an essential role to play to protect detainees’ rights. But the courts also tend to foster impunity, in part because cases of torture and ill-treatment in confinement are often poorly investigated from the start, whether due to incompetence, corruption or a reluctance to expose state responsibility.

When prison officials or police officers are implicated in violent incidents involving detainees, judicial authorities often accept the official version of events and move to dismiss cases. Another problem is that the very same security forces accused of wrongdoing are in charge of safeguarding evidence, which enables the potential manipulation of the crime scene.

In this scenario, the testimony of victims and witnesses is key to fighting impunity – and it is essential that they be protected from attempted threats, coercion or extortion. The active participation of family members in the case, in collaboration with experienced human rights organizations, is also very important. These actors often end up investigating themselves and propelling the judicial case forward, compensating for slack prosecutors. Finally, drawing public attention to what occurred, through protests and/or media advocacy, yields results as well.

Two emblematic cases of torture ended in convictions in 2015, thanks to these strategies to work around patterns of impunity. The first was that of Patricio Barros Cisneros, a 26 year old who was beaten to death by prison officials in January 2012 in front of his visiting girlfriend and other witnesses. The second case involved Luciano Arruga, a 16 year old who was tortured in September 2008 in a provincial police station that was not authorized for detaining anyone, much less a teenager. (Luciano went missing in January 2009 and his body was found nearly five years later, buried as a John Doe in a city cemetery; his death is still being investigated.)

Also last year, the provincial Public Prosecutor’s Office issued a protocol to guide prosecutors’ actions when torture against a detainee has been denounced, which contemplates the need to protect witnesses and safeguard the physical evidence found on site as well as the obligation to probe the responsibility of the penitentiary service. However, without proper training or the establishment of incentives and disciplinary sanctions to ensure the protocol’s implementation – and without effective oversight – the judicial response to torture will continue to fail detainees.

consequences of the sustained increase in incarceration

7

Eva Asprella and Marina García Acevedo

with the collaboration of Mariano Lanziano, Manuel Tufró, Victoria Darraidou and Juliana MirandaThe number of detainees in Argentina doubled between 1997 and 2014. A host of factors have prompted this rise, including the impact of legislative reforms that stiffened prison sentences and restricted judges’ ability to order people’s release, and the expansion of police faculties to detain people.

At least 69,060 people were detained in prison units nationwide as of December 2014, the last date for which official data is available. Pretrial detention is the norm as two-thirds of them do not have a final judgment. The state’s punitive policies mainly affect youth with low education levels: 60% of people detained in Argentine prisons are between 18 and 34 years of age; 34% did not finish primary school and 73% never started their secondary school studies.

In Buenos Aires province, which is home to the country’s biggest penitentiary system, the prison population hit a record high of 36,038 people in 2015, up 32% from 2007. The provincial incarceration rate exceeds that of some countries with high levels of imprisonment, such as Mexico and Venezuela. In addition, there has been a renewed surge in the number of people detained in police stations – in direct violation of an Argentine Supreme Court ruling.

Rising incarceration rates have led to more overcrowding, which negatively affects detainees’ living conditions and their access to rights. More specifically, it affects their health, increases violence and gives prison officials more power to make discretional use of resources and foster conflicts among detainees.

With regard to deaths in the provincial prison system, the penitentiary service has systematically attempted to hide its responsibility in different cases, many of which are willfully misreported as suicides. In addition, prison officials often fail to intervene when urgent medical care is required. “Health problems and the lack of medical attention explain 60% of deaths on average. Many of the illnesses that ended up being fatal were contracted during detention, and were not treated adequately. Diseases such as HIV and tuberculosis, which have been controlled for decades in society, persist in prisons,” the 2016 Report states.

To put an end to these human rights violations, the provincial government must lower incarceration rates, prevent violence and guarantee decent conditions. At the same time, the judicial branch must monitor detention conditions and urge the creation of an effective system for controlling overcrowding. Finally, it is crucial that the Provincial Mechanism to Prevent Torture be set in motion.

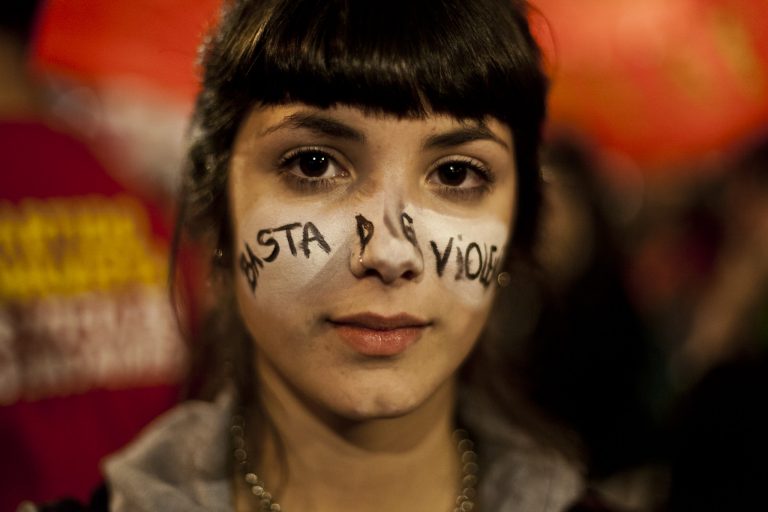

institutional violence against women and "ni una menos"

8

Edurne Cárdenas and Vanina Escales

the section on “Police and gender violence" was written by Juliana MirandaThe massive “Ni una menos” (Not one woman less) street rally in June 2015 marked a turning point in the agenda to fight gender violence. The movement’s central document, to which CELS adhered, focused on a variety of problems: women’s right “to say no”; the need to comprehensively address gender violence, moving beyond a security perspective; the ineffective judicial response to victims, demonstrated by the high proportion of women killed despite existing legal complaints and restraining orders; and the attempt by some journalists to explain femicides by focusing on a woman’s behavior.

These demands elevated the public debate and had a concrete impact in terms of government measures: several registries were created to track femicides and other cases of violence against women; a specialized prosecution unit was established; and the Federal Education Council moved to strengthen implementation of programs arising from the laws on sex education and on the comprehensive protection of women. This impressive wave of action revealed the tremendous lag that existed in protecting the human rights of a high percentage of the population.

The definition of institutional violence set forth in the Law of Comprehensive Protection of Women serves to analyze a series of problems that are pending in terms of public policy. The law defines this type of violence as “that which is carried out by officials, professionals, staff and agents belonging to any public body, entity or institution, which aims to delay, hinder or impede women’s ability to access public policies and exercise the rights set forth in this law.”

At CELS, we propose working on a gender agenda linked to institutional violence and centered on the penalization of abortion; the persistent problems that people who are victims of sexist violence face to access justice; trans and transvestite people’s access to rights; the incarceration of women along with their children, or for drug-related offenses, or in relation to crimes committed by their abusive partners; and femicides committed by police personnel.

Argentina has ratified international and regional conventions on the discrimination and subordination of women, understood as a human rights problem, as well as on gender violence. But the state dragged its feet on implementing the national action plan to prevent and eradicate violence against women, mandated by law, and the leading state body on gender policies has neither the authority nor the budgetary resources to be effective.

access to justice as a human rights matter

9

Andrés López Cabello, Margarita Trovato, Tomás Griffa and Diego Morales

Problems in access to justice affect a whole host of actors who are on unequal footing in the courts. However, most judicial officials are indifferent to the inequality among parties in a given legal case. This occurs, for instance, in litigation against indigenous or peasant communities for occupying lands, even when these same communities have turned to the judiciary to vindicate their rights vis-à-vis third parties or the state. The power asymmetries put them at a disadvantage within the judicial process. One example of this in cases related to the environmental impact on territories is that communities are often unable to finance the reports or technical studies required, which means they face serious difficulties to produce evidence.

We have also seen in recent conflicts how the judiciary has issued rulings that limit access to rights when different actors used the judicial system to block or condition the implementation of laws that sought to curb economic concentration or create mechanisms for environmental protection. This was true of the Audiovisual Communication Services Law, the implementation of which was suspended several times by judges before reaching the Supreme Court, and the law for protecting glaciers, which was halted for several years thanks to lobbying by mining giant Barrick Gold, which served to delay the execution of a glaciers inventory.

The judiciary tends to ignore manifestations of deep, structural problems (such as the obstacles that large segments of the population face to access legal services and the courts, largely for economic reasons), and it rarely takes into account the overall context when addressing conflicts. Similarly, judicial officials do not contemplate the inequalities that arise in the judicial process – and this fact should be at the center of debates about how to reform the justice system. From our perspective, judicial practices that only serve to worsen situations of discrimination and inequality must be transformed, and social conflicts and their actors must be taken seriously.

freedom of expression: discouraging prospects

10

Damián Loreti, Diego de Charras, Wanda Fraiman, María Clara Güida, Alejandro Linares, Luis Lozano and María Soledad Segura

team on project UBACyT 20020130100611BA, “Debates around freedom of expression”The December 2015 reform, by executive decree, of the Audiovisual Communication Services Law (LSCA in Spanish) drastically reduced the state’s role in regulating the system of audiovisual media. It also enabled further concentration of media ownership and eliminated mechanisms for civil society participation in decision-making bodies. Early announcements made by the new communications minister, Oscar Aguad, revealed the political conception driving these reforms: that in Argentina there is no media concentration and that market forces should govern these services.

Initially the government took control of the body charged with implementing the LSCA, and summarily removed its directors. However, before that decree had been published in the Official Gazette or even announced publicly, police surrounded the entity’s building and indicated that they “were waiting for the new authorities.” All of these actions violated the procedures for removal set forth in the law, which had guaranteed the right of defense – in compliance with the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Human Rights System.

Ultimately, via a third decree, the government dissolved that body and created the new National Communications Entity (ENACOM), whose members are limited to people appointed by the executive branch and by the three biggest blocs in Congress. This decree disbanded the federal councils established under the law to ensure participation by different sectors of society in the regulation of these services.

These reforms gutted key provisions of the LSCA aimed at promoting people’s communication rights and ensuring plurality: they eliminated limits on cable ownership and scrapped numerous obligations by cable companies while also easing restrictions on the accumulation of broadcast licenses and providing for their automatic renewal, among other measures. The autonomy of the ENACOM is also of grave concern since its members can be removed without cause and by decree. CELS has kept the IACHR and its Special Rapporteurship for Freedom of Expression apprised of these irregularities and requested the adoption of urgent measures to safeguard the rights of the Argentine people.