Why do some political actors sustain that the armed forces should intervene in aff airs other than their primary mission of defending a country from military attack? Are there security threats that can be equated with outside threats and that justify the use of military might inside borders? In order to respond to these questions, we must examine how the notion of “new threats” was constructed, who is promoting it as doctrine, and what these supposed dangers are.

In the 1980s and 1990s, a process of democratization put an end to the military governments that had proliferated in Latin America during the twentieth century. The “national security doctrine,” pushed by the United States and adopted throughout the Americas, was also abandoned once the ghost of Communism could no longer be used to conjure internal enemies. At the same time, democracy weakened the existing tensions between the countries of the region. War with a neigh- boring country, which had been the main hypothesis of military conflict for most Latin American countries, began to disappear from the realm of possibility. With nuances depending on the situation and history of each country, the armed forces generally began to lose relevance as political actors in the wake of democracy.

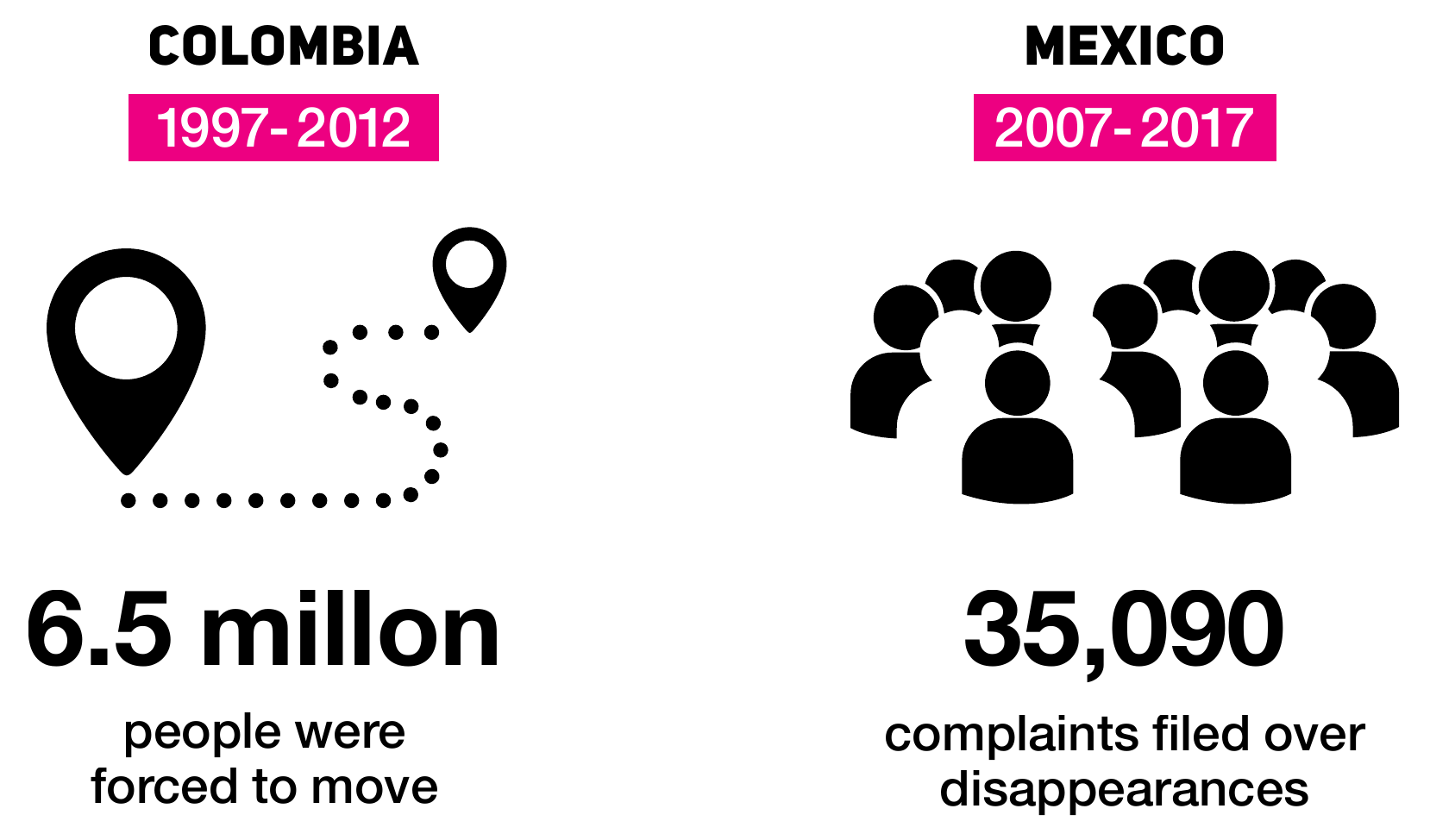

In the same period, the issues of crime and citizen security became central themes on the political agenda throughout the region. This led many countries to favor military involvement in “combating crime.” To varying extents in each country, the persistence of economic disparities and the expansion of illegal markets such as arms and drug trafficking—underpinned by increased consumption in the United States—contributed to transforming Latin America into one of the most violent regions in the world.

In this context, some US government agencies—including the US Southern Command—and lobbyists for the armed forces of the region created and spread the doctrine of “new threats.” This doctrine sustains that, in the absence of armed conflicts in the region, the principal threats to the stability of states now come from transnational organized crime, and in particular from activities linked to drug trafficking and phenomena such as poverty, migration and “populism.” In recent years, the United States has insisted on adding terrorism to this group. Viewed from this standpoint, the armed forces in each country should be re-trained to confront these heterogeneous issues that, in more than one case, are complex socioeconomic phenomena.

The reason why these problems should be met with a military response is not quite clear. In some cases, it is argued that these are transnational phenomena, as if this were synonymous with foreign military aggression. In other instances, it is posited that, in the absence of any potential scenario of military conflict, the armed forces should be turned into a sort of police force so as not to waste resources. In all cases, those seeking to convince the authorities and public opinion that there is no diff erence between citizen security and national defense use these “new threats” as their central argument. In that sense, this position represents continuity with the national security doctrine. Various factors explain the spread of this paradigm and the institutional and policy transformations that it has brought about in terms of security and defense.

The fight against drug trafficking has been at the center of many countries’ political and electoral agendas, and a string of security responses have been implemented, often including the internal use of military might. Even after proving ineffective and conducive to the intensification of violence, these policies usually have relatively solid social backing. This explains to a large extent why the drug trade has been one of the greatest social concerns associated with crime and violence. It awakens a social panic that is not unconnected to the prohibition of drugs and their historical conceptualization as a societal evil that must be “combated” at all costs.

In contrast, the terrorism agenda in the majority of countries is not associated with any widespread societal concern. Its presence in defense and security discourse and programs is more closely linked to the needs of hemispheric diplomatic agendas and bilateral relations with the United States. In some countries, anti-terrorism laws have used this agenda to persecute and stigmatize groups and social conflicts.

When incorporated into public policy, the notion of “new threats” leads to the militarization of domestic security, the depiction of social issues such as poverty and migration as security matters, or both things at once. This involves the expansion of the state’s capacity to carry out intelligence-related tasks or exchange information across different state agencies. The new threats, drug trafficking especially, are presented as justification for investigative techniques and forms of surveillance supposedly aimed at criminal groups, but which often are used against political opponents or other social actors and impact the rights of assembly, participation, protest and privacy. There has also been a backdrop of policy reforms involving the weakening of due process, whereby guarantees are reduced or eliminated for certain crimes that supposedly require exceptional responses.

The construction of “narco-terrorism”

The vague definition of “threats” and the lack of a serious diagnosis foster a scenario in which the issues encompassed by this agenda are constantly expanding, and the definitions and solutions shift from one problem to another. A good example is the category of “narcoterrorism” increasingly used by some US agencies and other regional actors.

The term “narco-terrorism,” used as an equivalent to “narco-guerrilla,” became common currency back in the 1980s in Peru to characterize the Shining Path. It was later adopted to describe the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). According to the US Department of Defense, “narco-terrorism” refers to acts of violence—murders, kidnappings, bombings—committed by drug traffickers to cause disruption and divert attention from their illegal operations. The US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) uses another definition: “narco-terrorism” is considered a sub-dimension of terrorism, where there is evidence of participation by individuals or terrorist groups in activities associated with the growing, manufacture, transportation and distribution of drugs.

After the September 2001 attacks on the United States, the idea of “narco-terrorism” was used to broaden the scope of the definition of terrorism. For example, in 2004, the former executive director of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) affi rmed that “fighting drug trafficking is the same as combating terrorism.” In this same vein, the US House Committee on Homeland Security proposed in 2012 that organizations devoted to drug trafficking be automatically classifi ed as terrorist groups, arguing that this would generate greater capacity to counter their threat to national security. In March 2017, more than 400 people from 14 countries attended a seminar on “Transnational Crime and International Terror Networks as Hybrid Threat Factors,” organized by the Colombian Ministry of Defense with support from the US Special Operations Command South. According to the director of Colombia’s School of War, hybrid threats are “the combination of conventional and non-conventional threats.” “In a conventional war or threat, we know who the enemy is... Something that is non-conventional acts in irregular ways, we do not know where to fi nd them, we do not know who the enemy is,” he explained.

The term “narco-terrorism” suggests that there is a symbiotic relationship between two phenomena, a relationship that empirical evidence rarely confi rms. At the same time, it overestimates the importance that drug money has on the financing of terrorism. explicó.

At the regional and global levels, the confl ation of drug trafficking, terrorism and other criminal networks enables an agenda of militarization and restrictions on rights that in the United States and Europe is associated with the “war on terror,” and which is also promoted in countries where there is no scenario of terrorist threats. Finally, the association drawn between both phenomena does not lead to developing better policies to address either of the two problems.

The demarcation between defense and security

Over the past 30 years in Latin America, two opposing tendencies have been at odds with each other when it comes to how state violence is exercised. The first is aimed at establishing a clear distinction between security and defense and taking power away from the armed forces as a political actor, as a condition for the democratization of the region. The second follows a recipe from the United States, according to which the armed forces must continue to intervene in security issues, because military threats have ceased.

In general terms, and with local nuances, it can be said that in the northern part of the region—Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean—the latter tendency has dominated. And in the Southern Cone, the distinction between security and defense has been an important aspect of recent political history, cemented in a broad consensus regarding the importance of limiting the armed forces’ signifi cance as a political actor and re- stricting its scope of authority to its principal mission. In the Andean countries, the armed forces tend to be multifunctional since, in addition to their traditional role of defense and intervention in security matters, they fulfi ll other functions related to social issues, infrastructure and transportation, and even participate in administer- ing state companies.

At the same time, an analysis of citizen security policies shows that even within the countries of the Southern Cone, there are tensions. On the one hand, there is a tendency toward police reform based on the notion that it is an armed civilian corps and on promoting a vision of police as workers and not soldiers. On the other, there is an opposing trend that, through the creation of heavily armed tactical teams used for urban patrols, is conducive to differential security strategies for poor neighborhoods that are subject to territorial occupa- tion. One component of the pendulum eff ect between citizen security and hardline policies is this back and forth between demilitarization and remilitarization of the police corps and their deployment and intervention techniques.

The geopolitical dimension

The issue of “new threats” and the militarization of internal security have to do with regional geopolitical matters. The adoption of this doctrine is linked to Latin American countries’ failure to discuss and develop a national and regional defense policy that is autonomous from the United States. In choosing this route, the defense dimension tends to disappear as it is subsumed under strategies of militarized security dependent on the directives and aims of the US military apparatus.

This shift has intensified since some governments suspended their participation in the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), a forum that, despite its problems and tensions, had functioned as a platform for posing the need for a regional defense policy and a departure from the doctrine of new threats. The governments that came to power in the past fi ve years in countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Chile have chosen a new, more explicit alignment with US policy, instead of strengthening autonomous regional instruments.

An important part of this realignment is the adoption of the “new threats” agenda and the “war on terrorism” promoted by the United States. Although the adoption of a drug policy based on a prohibitionist paradigm and warlike approach to supply is not the only problem associated with the militarization of security forces, it does constitute one of its core points of anchorage and development, along with the war on terrorism.

The toughening of security policies in Latin America

The doctrine of new threats has an impact on the security policies of Latin American countries in that it encourages a toughened state response to diverse criminal phenomena and even social problems unrelated to any crime-linked dynamics. This process consists of two trends. One, the militarization of security gets the military forces involved in police tasks. The second involves the reorientation of the traditional components of the criminal justice and security systems—the police, laws and criminal codes, the intelligence apparatus—to address problems redefi ned as matters of national security and to pursue internal enemies.

In some countries, both trends can be observed; in others where the role of the armed forces continues to be limited, the alignment with the doctrine of new threats is manifested primarily in how the police function and in regulatory changes.

The militarization of security

The police corps is based on the same premise as the military in the sense that they are the instruments that embody and implement the state’s monopoly on exercising legitimate violence. But the missions of security and defense are qualitatively distinct in terms of training, skills, equipment, and principles of action and use of force, among other matters.

In recent years, the emergence of citizen security paradigms and “community approaches” to police work has sought to further the conceptual diff erence between the security and defense spheres. But in the same period, the doctrine of new threats has functioned as an opposing force since it seeks to do away with the distinction between security and defense and promote the militarization of security.

A series of indicators can be used to assess the existence or the intensity of militarization processes in each national context.

1. Regulations

This refers to the existence or absence and, depending on the case, the weakening or strengthening of regulations that distinguish the roles of the police from those of the military. Thus, legislation that endorses the intervention of the armed forces in internal security entails more militarization, while the regulation and differentiation of the functions of national defense and domestic security is a step in the opposite direction.

It is essential to also assess whether mechanisms have been put in place to get around existing provisions. This can be observed, for example, in the use of lowerranking or internal regulations aimed at exploiting the ambiguities in national legislation to involve the armed forces in security tasks.

2. Joint organization

The way security and defense systems are organized and function can be observed in specific institutional arrangements. For instance, the institutionalization of joint decision-making by the military, police and civilian entities or the exchange of intelligence between the police and the military indicate a move forward in terms of militarization. The same is true when there are joint operational groups made up of military and police forces with military training in security matters.

3. Military participation in anti-crime actions

The most advanced degree of militarization involves the direct participation of military forces in anti-crime operations.

The experience in Latin America with the militarization of drug policy allows for identifying three distinct scenarios of military intervention: in rural contexts, in the forced eradication of illegal crops, for example; in urban settings, to patrol high-crime areas, carry out raids and confront criminal gangs; and third, in operations to intercept land, air and sea or river traffic associated with illegal activities. 7 In addition to these, there is military intervention in criminal intelligence work, especially after the incorporation of terrorism into the new threats agenda.

The justifications

A variety of arguments are usually enlisted to justify military intervention in security. The basic justification—because it is the reason for being of the new threats doctrine—is the idea that wars between states no longer exist and that threats arise from drug trafficking, other crimes or socioeconomic problems. According to this viewpoint, Latin America’s armed forces are idle and should be tasked with protecting internal security. This same approach served to involve the military in other functions further removed from security but equally outside its core missions, such as the safeguarding of geostrategic points or assisting in citizen aid during natural disasters.

At the same time, society’s concern with violence and crime has been enlisted as an excuse for successive governments in the region to deploy the military as an anti-crime measure. These policies are often designed and executed in keeping with short-term political or electoral aims that resort to the armed forces as a way to reinforce the idea that the “war on crime” is being stepped up. In line with this, policies of militarization are usually grounded in the view that sustains that the police’s operational capacities are too overwhelmed to confront the increasingly complex problems of security. The strategies for taking on drug trafficking and other “national security threats” are usually presented in warlike terms, in conjunction with pessimism about the state’s capacity to address them. This contributes to the legitimization of all kinds of “combat” measures, such as the intervention of the armed forces in police tasks, in addition to the use of elite tactical groups for tasks formerly carried out by ordinary police. Police corruption and the notion that the armed forces are not “contaminated” are also arguments used to justify military intervention.

The insistence on “new threats” often works as a political communication strategy to distract attention from other salient phenomena such as state collusion (police, political, judicial and even military), without which the same illegal markets that are deemed to be state threats could not prosper.

The negative consequences

Military involvement in security tasks brings political and institutional problems. First, this policy has a direct impact on the de-professionalization of the armed forces, whose members have been trained and equipped for complex issues related to national defense, not for resolving the problems of crime. And at the same time, recourse to the armed forces overshadows the structural problems of the police, both in terms of corruption as well as ineffectiveness. Thus, military participation becomes an excuse to avoid the deeper police reforms needed in the region.

In the second place, experience has shown that using the armed forces for police work usually leads to the erosion of the military as an institution. This occurs because the military gets involved in the same processes of corruption affecting the police, under different modalities: collusion with the members of criminal networks, development of para-state groups associated with members of the military, or direct implication of military officials in illegal markets. For example, former members of the special unit of the Guatemalan Army known as the Kaibiles were recruited by the Mexican cartel the Zetas to instruct them in the specific techniques and knowledge acquired during their military training.

Third, assigning non-primary missions to the armed forces implies an expansion of military presence in the political system and in society. This is particularly risky in countries with relatively new and unstable democracies, and where the military forces retain multiple duties in internal security matters after the restoration of democracy. In many cases, the military continues to hold weight with a broad capacity to impact political and social life and shape how conflict management strategies are defi ned. Militarization tends to grant more autonomy to the military forces and upset civic-military relations, reducing the political stewardship of civilian power as a result.

Finally, involving the military in internal security serves to weaken the very defense capabilities for which it was trained. Hence, the strategy of militarizing security may jeopardize the strengthening, modernization and sovereignty of policies designed to defi ne national defense strategy and the survival of the state. This situation enshrines the hegemony of the United States in the region, given that it reinforces its influence on Latin American countries. At the same time, the militarization of security has negative impacts on human rights, as analyzed in Chapter 3 of this publication.

The reorientation of the criminal justice system and security policies

Juan Gabriel Tokatlian observes that the evolution of drug policies since the instatement of the international prohibitionist regime at the beginning of the twentieth century entailed, among other things, “securitization” —converting a health problem into a security problem— and, going a step further, militarization or involvement of the armed forces as a tool of the prohibitionist paradigm.

If the “securitization” of the drug problem is a long-standing phenomenon in the region, the inclusion of this problem in the doctrine of new threats constituted a fresh push for tougher policy that can be seen not only in the militarization of security but also the reorientation of the security and criminal justice systems. The latter implies a shift away from the notion of citizen security, as understood from the standpoint of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), for instance, which defi nes it as “an approach that focuses on building a stronger democratic citizenry, while making clear that the central objective of the policies established is the human person, and not the security of the State or a given political system.”

According to the doctrine of new threats, the state and a certain public order are subject to protection. With the restoration of national security as a priority, even in countries where the armed forces have not intervened in internal security, phenomena of police militarization occur as well as regulatory modifi cations that open the door to labeling certain groups or actors as internal enemies or threats to state sovereignty. At the same time, the opaqueness and secrecy that typify the military and defense have spread to the security forces and criminal intelligence routines, which cease to be accountable, as if revealing any information, or any assessment of their modes of operation, could constitute disclosure to an unknown “enemy.”

The application of military patterns and ideas to the organization of the internal security system mainly affects police institutions. The processing of crime through a military lens influences how the police and other crime-control agents think about their strategic functions, the institutional structure they adopt, the decisions they make and other organizational elements that lead the police to act in accordance with patterns in keeping with the military model.

One indicator of police militarization is the creation of special units or tactical or elite groups for routine tasks like detentions, raids, confi scations or other operations, and the expansion of their functions within the security forces.

The equipment and technology the forces use are also indicative, especially when related to the expanded use of military weapons in internal security contexts. Military equipment has greater firepower than the police’s and the training it requires is much more complex and specific. Its high levels of harmfulness and lethality make such equipment inappropriate for engagement with citizens.

Finally, interventions involving the territorial occupation of poor neighborhoods have been on the rise in recent years as a priority security strategy in different countries. With important diff erences, these occupations are presented as operations to “recuperate” areas supposedly lost to drug trafficking and crime. The absence of any serious assessment of these policies ensures that they continue to be applied and recommended, despite their negative impact on the population in these areas.

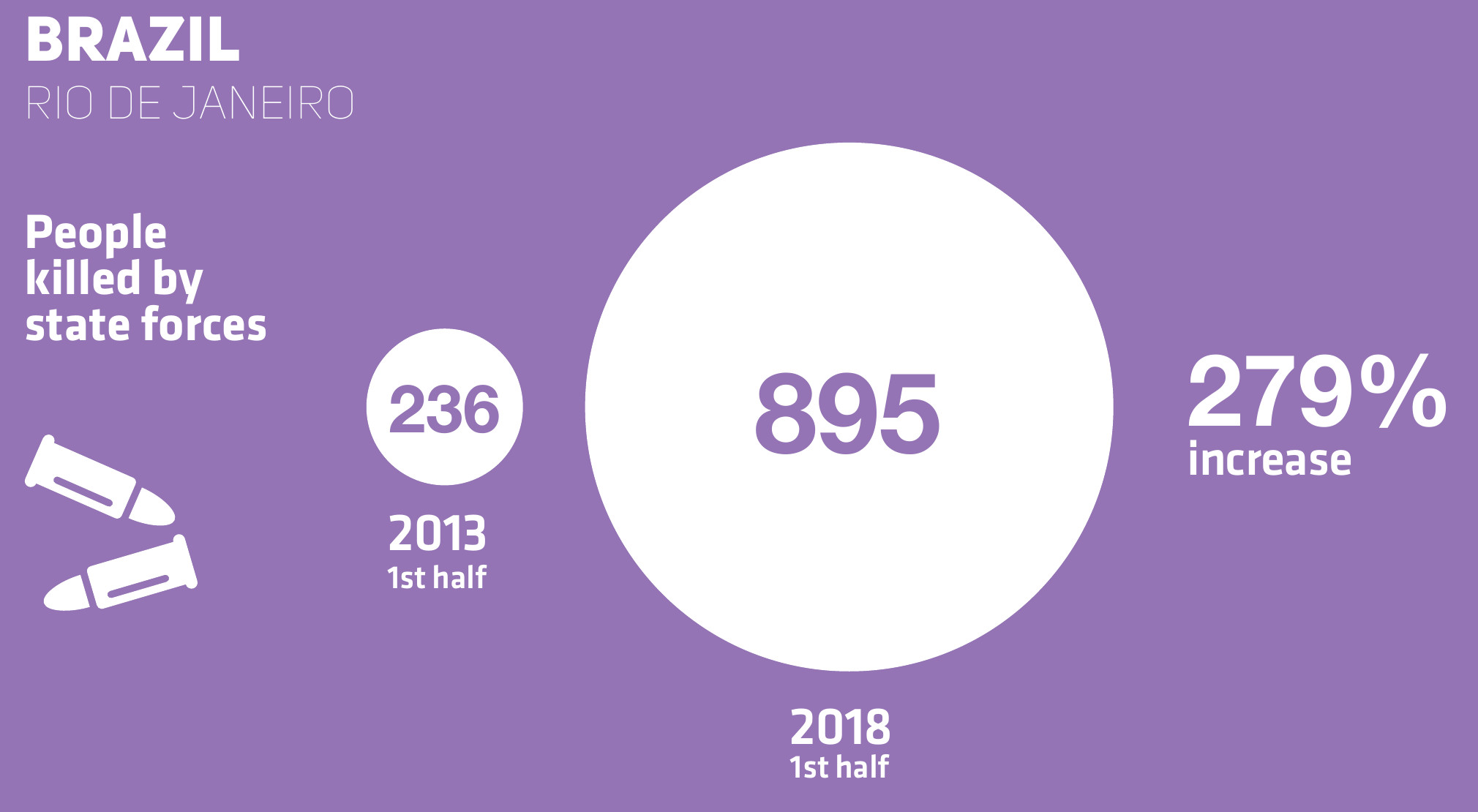

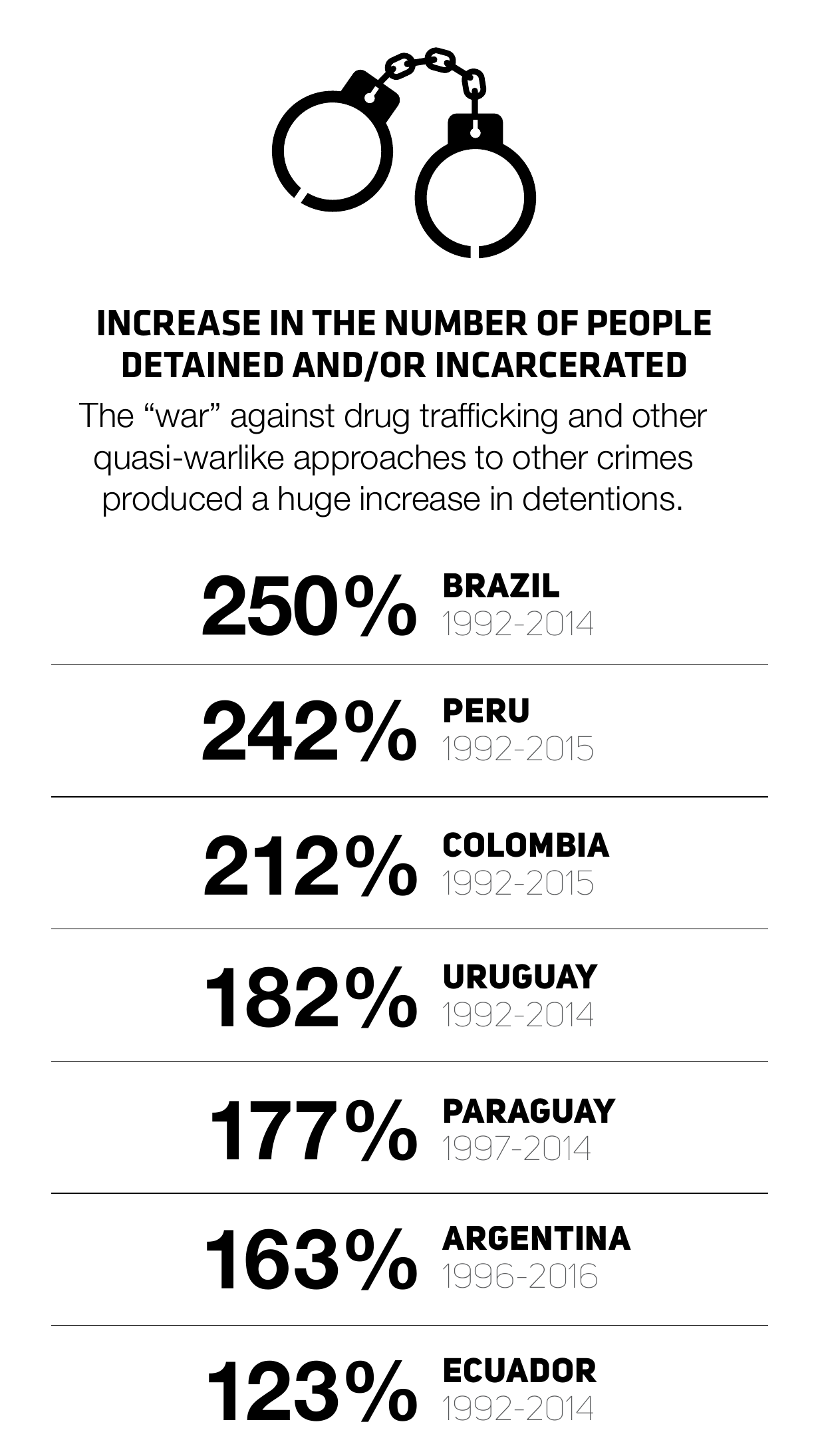

The exponential growth of the prison population in the region and critical situations of overcrowding are also in good measure a result of the toughening of antidrug policies. If the doctrine of new threats illustrates the geopolitical dimension of this phenomenon, the diverse “wars on small-scale drug dealing” and even the criminalization of drug users seen all over the Americas have a troubling impact on neighborhoods, streets and prisons. This impact combines extreme prohibition, the construction of internal enemies, high-profile communications campaigns and an approach to crime as a matter of national security—all of which constitutes a risk to the entire region.

The deployment of “combat” strategies has proven to be ineffective when it comes to reducing drug trafficking or the violence associated with criminal behavior. On the contrary, these measures tend to reproduce the dynamics of social and institutional violence that characterize the region. Without disregard for the potential seriousness of security problems like drug trafficking or terrorism, these phenomena cannot be addressed with the same strategy, because they are not manifested in the same way in every country. The result of these interventions is, in all cases where it has been attempted, the failure to solve the problem that prompted the decision to promote “war” tactics in the first place. Despite the fact that the eff ects of these policies are very hard to reverse in the short or medium term, their toughening and militarization persist and are on the rise, underpinned by a series of regional processes, although with national specificities.

ARGENTINA

DANGEROUS HEADWAY MADE BY THE PROHIBITIONIST COALITION

Argentina is one of the few countries that have sustained a clear policy separation between national defense and domestic security. The Cristina Fernández de Kirchner administration opted for military intervention to protect the country’s northern border, enlisting the Fortín I and II and Escudo Norte operations to reinforce air and land surveillance as a strategy in the fight against drug trafficking. This decision was related to another to reassign the National Gendarmerie—the federal security force in charge of border control—to patrol urban centers and poor neighborhoods. That intervention was de facto, without a legal framework. During the government of Mauricio Macri, the trend to authorize military intervention in internal security has deepened and been framed in an explicit policy agenda aligned with the “new threats” doctrine and a prohibitionist and punitive perspective. The current government has put the war on drugs and combating terrorism at the center of its agenda. This discourse is a political break with the principle of demarcation between defense and security that legitimizes military intervention in security and renounces the development of a national defense policy and professionalization of the armed forces.

This shift has been reflected in various measures. Right after taking power, the government declared a security emergency to be able to intervene in these new threats, which included a decree authorizing the downing of aircraft. In 2018, the administration amended Decree 727/06 regulating the National Defense Law: it eliminated the reference to military aggression by other states as the sole cause for military retaliation, expanded its intervention under the modality of “logistical support,” and authorized the possibility of the armed forces safeguarding “strategic objectives” such as nuclear facilities or natural resources. In the same vein, the government repealed the military directives in force and replaced them with a plan related to the “new threats” and placed Venezuela at the center of regional instability.

This transformation reinforced the influence of the United States that, in drug trafficking matters, has been channeled through the DEA since the 1990s. The prioritization of the US agenda was made explicit in meetings and high-level visits to increase cooperation, in particular with the State Department and the Southern Command, and in exchanges on training and arms deals, mainly with Israel. But this agenda is not entirely an external imposition since it also incorporates the worldview of local elites. It is this local prohibitionist coalition that sustains, without any data to corroborate it, that Argentina is in a situation of emergency caused by the drug market and the influence of terrorism that requires measures that go beyond the capacity of the security apparatus.

This approach has not translated into military deployment in the country, both because of social and political resistance—in good measure resulting from the military’s actions during the last dictatorship—as well as from the armed forces themselves, which are hesitant to assume this new policing role without a budget or real modernization plan.

This “gestural militarization” has limited operational scope but does create a scenario conducive to the militarization of security and tougher policing. In Argentina, what happens in practice is a transfer of resources from the defense apparatus to security.

Now the armed forces are part of the country’s security apparatus in that, whether they actively intervene or not, they will be taken to the border to replace the police forces deployed in urban centers. This type of patrol duty is presented as utterly harmless. However, it opens many questions, such as its relationship to military intelligence, a practice that is prohibited by law. Prohibitionist, militaristic tendencies are expressed through policy and extremely punitive, security-focused rhetoric in the face of social issues such as migration, land disputes and social protest.

Thus, the “war” on drugs and terrorism is used as justification for blowing the security apparatus out of proportion and expanding punitive policies and actions. Argentina has a per capita police presence nearly triple that recommended by the United Nations—300, compared to nearly 900 per 100,000 inhabitants in Argentina—but the prohibitionist coalition insists this is still not enough. At the same time, based on the never-substantiated idea that the police are overwhelmed in their duties, the intervention of elite police units is sanctioned. Furthermore, the intelligence agenda has been expanded in the name of national security, incorporating new procedural tools for surveillance, cooperation and exchange of intelligence information between countries, along with the expansion of the logic of secrecy. All of this is already having an impact on a sustained increase in incarceration rates (especially for minor drugrelated offenses such as small-scale dealing), on greater state surveillance and on reports of illegal intelligence.

The toughening and militarization

of security policies in Latin America

The processes involved in the toughening of security in Latin America are varied but have certain features in common that make for a regional trend. The policies implemented indicate direct influence by the United States in this agenda, but there are also any number of local military and civilian stakeholders whose political agendas are aligned with these prohibitionist and punitive militarized strategies.

Washington encourages Latin American states to improve their defense capabilities in the face of phenomena characterized as threats to the region and, above all, to the United States. In other words, it seeks to reinforce and broaden its own security and military apparatus through joint conjuring of these hypothetical conflicts in the name of greater stability in the region.

This influence is not merely rhetorical, but is a reality in terms of cross-border information flows, reforms and concrete institutional practices that are repeated across different countries.

A clear example is bi- and multilateral cooperation in terms of financial aid for security matters, training of police and military personnel, and weapons acquisition. These processes involve the expansion of the weapons industry in countries with violent military and security forces and with large illegal firearms markets. The main justification for these exchanges has been to “fight drug trafficking” from a perspective of controlling supply, but the issue of terrorism also forms part of the exchange agenda. In recent years, countries like Colombia have been the centerpiece of such exchanges, in a sort of outsourcing of the training of armed forces, police and officials. When it comes to training, there have been soldiers training police, as well as armed forces involvement in internal security matters. These dynamics of socialization and training are key aspects of the militarization process, because they blur the line between the duties of one force and the other.

Another relevant aspect is the string of regulatory changes that broaden or authorize military intervention in aspects of internal security. Depending on the country, the laws can either back or limit the use of the armed forces in security tasks. Countries that already had a military tradition have readily adopted prohibitionist thinking with regard to toughening the state’s response. In others, the military was given a new role.

In recent years, treating crime-related problems as sovereign or state security threats has resulted in a series of reforms that give the armed forces a more significant role in the domestic setting. Nearly throughout the region, anti-terrorism laws were passed, some authorizing military force in security tasks and the downing of planes, as well as rules aimed at giving immunity to the military and police for possible human rights violations.

In some countries, these processes were deepened to the extent that they ended in military deployments for anti-drug and anti-terror operations, and to a lesser degree for urban patrol tasks, anti-crime programs or border operations. In countries where this deployment reached a significant scale, participation by the armed forces in these tasks was institutionalized in settings for joint decision-making with civilian authorities (police, judicial and migration) or in mixed operations groups and joint task forces.

At the same time, other processes have evolved in the region that do not entail direct participation by the military in the pursuit of crime, but that transform the design and implementation of security policies and law enforcement.

Adopting the ideology of national security, the notion of a “war” on drugs or “combating” terrorism all serve to reorient the security, prison and intelligence systems. This is manifested for instance in the training of local police in theories and practices patterned on the military, which in turn have an impact on the use of excessively violent and aggressive police tactics.

Cooperation with the United States

Aid programs and flows

The funds flowing from the United States to the region increased steadily between 2001 and 2007, and then diminished consistently. In part, this was the result of general budget cuts for foreign aid from the United States after the Barack Obama government tried to reduce the defi cit from the 2008 fi nancial crisis. There were two exceptions to this reduction: Central America, which had a financing peak in 2016 that tripled the funding received in 2015, and the Andean region, which maintained a stable level of financing between 2011 and 2017. This financing varies at the sub-regional level according to US strategy and the regional geopolitical order.

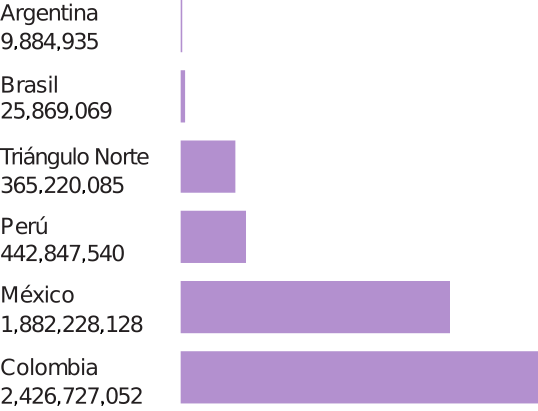

US financial aid for security, cumulative by country 2010-2018 (in USD)

Source: Author’s compilation based on data from Security Assistance Monitor.

The first foreign aid budget under the government of Donald Trump, submitted for congressional approval in May 2017, requested an abrupt cut in State Department financing and development aid for Latin America and, to a lesser extent, also in military and security-related aid. With respect to the previous year, it requested cutting a third of expenditures for Mexico, Colombia and Central America. However, in March 2018 Congress rejected the budget and kept the financing levels similar to those from 2017. For 2019, the White House again asked for cuts in aid to Latin America.

The money is channeled through an array of fi nancial aid programs to diverse initiatives in each country. In the last three decades, the majority of these programs focus on or have some drug-related component, always from a prohibitionist perspective aimed at controlling supply.

US-Latin America aid programs

| Program | Start | Authority | Activities financed | Recipients | Amounts (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign Military Financing (FMF) | 1961 | State Dept. and Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) | Purchase of articles and defense services from the United States. Weapons training. Funds cover purchases through Foreign Military Sales (between states) and Direct Commercial Sales (between states and businesses). | Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Peru. | 82,665,000 (2017) |

| International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) | 1961 | State Dept. | Equipment, training and services to counter drugs, crime and money laundering. Cybersecurity, police and judicial reform. Financed military equipment for Plan Colombia and the Merida Initiative and aerial fumigation in Colombia. | Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Haiti, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru. | 302,775,000 (2018) |

| International Military Education and Training (IMET) | 1961 | State Dept. | Military and police education and training. Promotes joint work between foreign and US armed forces and those of NATO countries. The IMET finances courses on defense resource management, military justice and human rights, civilian oversight of the military and military-police cooperation in anti-drug operations. | Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela. | 106,325,000 (2018) |

| Section 1004 Counter-Drug and Counter-Transnational Organized Crime | 1991 | Defense Dept. | Military and civilian training in anti-narcotics operations and to counter crime networks. Transport, infrastructure, detection of substance trafficking, air and/or land reconnaissance, intelligence and information analysis. | Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Uruguay. | 185,411,000 (2017) |

| Combating Terrorism Fellowship Program (CTFP) | 2002 | Defense Dept. | Training of foreign military and defense and security officials in US military institutions on lethal and non-lethal techniques. Seeks to standardize a vision of terrorism and counter-insurgency and create a global network of professional experts to support US actions. | Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay | 2,911,000 (2016) |

Source: Author’s compilation based on data from Security Assistance Monitor.

Aid to Colombia, Mexico and Central America

| Select programs | 2000 | 2008 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andean Counterdrug Initiative - Colombia | US$ 832,000,000 | US$ 245,000,000 | N/A |

| Merida Initiative | N/A | US$ 400,000,000 | US$ 139,000,000 |

| CARSI | N/A | US$ 60,000,000 | US$ 348,500,000 |

Source: Author’s compilation based on data from the Central America Monitor of the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) and the Congressional Research Service.

Some programs provide aid to countries or specific sub-regions, such as Plan Colombia, which began in 2000 to reduce the production and export of illegal drugs and to strengthen the counter-insurgency campaign against the FARC. But a good portion of the funds for Plan Colombia were channeled through the Andean Counterdrug Initiative (ACI). As of 2009, the United States began financing Colombia through other programs. At least since the turn of the twenty-first century, it is the Latin American country that has received the most US funding, regardless of the political orientation of the US government. As for its impact on reducing supply, the effectiveness of these actions is dubious: according to data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), between 2016 and 2017 the area of coca cultivation expanded by 17%, reaching a record 171,000 hectares.

Other programs focused on specific regions are the Merida Initiative, which supports the purchase of military equipment from US corporations as well as training and funds for the Mexican police and armed forces, and the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), which fi nances equipment, training and technical assistance for operations to combata variety of criminal phenomena in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador (Northern Triangle). In recent years, these countries were the recipients of more funding, in US response to high levels of crime and violence and the migration crisis that displaced thousands of people who headed toward the southern border of Mexico. At the same time, cooperation with Mexico has declined.

US financial aid is regulated by the Leahy Law, which prohibits the training of any foreign security forces or units implicated in human rights violations and which is incorporated into the national defense laws. However, financing channels exist that are not covered by the law and are often used to elude it. The State Department and Defense Department apply this provision to most forms of training, but not to all forms of cooperation, such as technical assistance, intelligence sharing or joint military exercises. Arms sales made within the Foreign Military Sales program are also not subject to these restrictions.

The aid programs do not have outcome indicators or standardized evaluation mechanisms to measure whether they are effective at meeting their objectives. US embassies function as interlocutors on the local situation and have great decision-making power over what is considered priority in each country, the evolution of programs and the power to decide what works. In general, the formal requirements for disbursing funds are not well defi ned and low standards of compliance are common. This is combined with reduced transparency in aid and military operations. Between 2010 and 2018, more than US$1.3 million were allocated to countries without specification through a general budget allowance for the “Western hemisphere.” In 2010, these unspecifi ed funds represented 5.5% of the total budget allotted to Latin America. Under the requested amount for 2019, this percentage would ascend to 42.4%. In parallel, the Defense Department’s budget for foreign military assistance tripled between 2008 and 2015, in comparison to 23% for the State Department. It is clear that the real amount of financing sent to the region is not available to the public.

Training and education

The training of military and police is central to any analysis of militarization processes, in particular with regard to police training by the military, on the one hand, and military forces being trained in internal security matters, on the other, because the distinction between the functions of one force and the other is blurred.

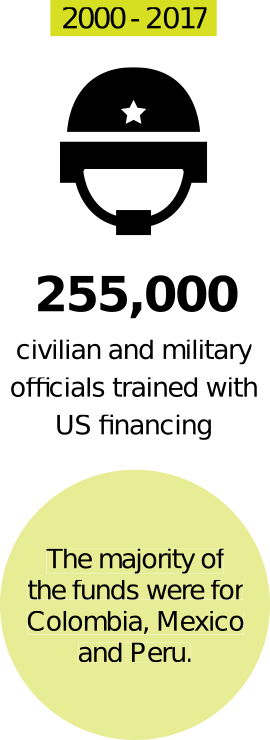

This is a fundamental component of US foreign policy for Latin America, which receives a fifth of all training supplied by the United States to foreign officials. Between 2000 and 2017, more than 255,000 officials (civilian and military) were trained with US financing.

Between 2011 and 2016, the number of Latin American security and military officials trained grew by nearly 67%. This increase is not uniform across all countries: since 2000, Colombia has received the greatest portion of this training, followed by Mexico and, much further behind, Peru. In 2017, training fell in nearly all countries except Brazil. The majority is financed through the Section 1004 program, which is mainly focused on counter-narcotics initiatives: in 2016, more than half of Latin American officials trained were instructed in this area.

Other training is done through the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC), the name given since 2001 to the School of the Americas, which trained agents in counter-insurgency techniques, sharp-shooter skills, military intelligence and interrogation techniques in the framework of the doctrine of national security. Graduates from this academy committed human rights violations during the Latin American dictatorial regimes. Currently, WHINSEC is the US Department of Defense’s main combat academy in the Spanish-speaking world. In addition to traditional military training, the institute incorporates courses on democratic sustainability, peace operations and human rights, in line with the principles of the Organization of American States. Between 2009 and 2015, more than 900 civilian and military officials from Peru, Brazil, Mexico and Argentina were trained there.

Training of officials from Colombia, Peru, Brazil, Mexico and Argentina at WHINSEC, 2009-2015

| Programs that financed the courses | Type of training | |

|---|---|---|

| Colombia | Foreign Military Financing, INCLE, IMET | Combating transnational threats, analysis of intelligence and narco-terrorism information, joint operations and anti-narcotics, peace operations. |

| Peru | Section 1004, IMET, INCLE, Foreign Military Financing | Anti-narcotics operations, intelligence, combating narco-terrorism and transnational threats. |

| Brazil | Section 1004, IMET, Regional Centers for Security Studies | Analysis of narco-terrorism information, anti-narcotics operations, joint operations and engineering, medical aid. |

| Mexico | Section 1004, IMET, INCLE | Transnational threats, anti-narcotics operations, information analysis, human rights, medical aid, joint operations and engineering. |

| Argentina | Section 1004 | Analysis of narco-terrorism information, medical aid, anti-narcotics operations. |

Source: Author’s compilation based on data from Security Assistance Monitor.

The Colombian police and military have also provided training to other countries. These officials were trained in US cooperation programs and are currently used to outsource training. This policy of “exporting security” has become a fundamental component of Colombian foreign policy, although it in large part abides by a US strategy, the primary eff ect of which is to confer new roles on countries with a certain degree of affinity. Much of this training is part of the US-Colombia Action Plan on Regional Security (USCAP), signed in 2012 with the specific purpose of “exporting” the capacities built in Colombia, especially on policies to counter crime, drug trafficking and terrorism, but also on human rights and institutional strengthening, despite the human rights violations committed by the Colombian forces in the context of their interventions against crime. Since 2013, USCAP has trained 5,600 military and police officials from Panama, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic in matters such as river operations, naval intelligence and infantry tactics.

These trainings pose problems of transparency and accountability with regard to their specific content, the participants in them and the mechanisms through which the budget is allocated to avoid having to submit it for US congressional approval. Nor is the impact of “skills exportation” on the local reality evaluated.

Outsourcing is a way of eluding the restriction established under the Leahy Law that prohibits cooperation with security forces that have committed human rights violations. The current chief of staff under Trump admitted this in 2014 before Congress when he said “the beauty of having a Colombia” to train the Central Americans was being able to elude “restrictions on working with them for ‘past sins’”.

The armed forces of many countries participated in joint training exercises with each other on internal security matters, generally on anti-drug trafficking actions, or to foster civil-military cooperation. One of these exercises is Operation Hammer, led by the Southern Command as part of a US strategy to contribute to multinational operations of detection, monitoring and confi scation of drugs and weapons in Central America. This operation created in 2012 involves the US Navy and Coast Guard and other police and military agencies from 14 participating countries.

Other military exercises that train Latin American armed forces in internal security tasks are UNITAS, PANAMAX, Teamwork South, RIMPAC, Bold Alligator and Fuerzas Comando.

• Bold Alligator began in 2011 and involved military training for amphibious marine operations against “new threats.” According to the Department of Defense, “the fight today is a mixture of threats on a non-linear battlefield (...). We are fighting in a domain made up of the marine, air, land and cyber spheres.” This training was done in 2017 in the state of North Carolina, with participation by Mexico, Peru, Brazil, France, Germany, Canada, Spain and the United Kingdom.

• Fuerzas Comando is sponsored by the Southern Command under Special Operations Command South (SOCSOUTH). Around 700 military, civilian and security officials participate. It is composed of two blocks: a technical and practical skills competition, and a Distinguished Guests Program provided through the Combating Terrorism Fellowship Program (CTFP) focused on “combating terrorism, organized crime and drug trafficking.” In 2018, it was held in Panama with participation by Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru and the countries of the Northern Triangle, among others.

• Teamwork South is a biannual naval exercise created by the Chilean Army in 1995 jointly with the United States, which has expanded the range of operational exercises. Its current objective is to train Chilean and foreign forces and to standardize the approach to terrorism, drug, contraband and human trafficking. In 2017, it was held between the areas of Talcahuano and Coquimbo, Chile.

• UNITAS is the longest-running US Navy maritime exercise, in which Argentina, Mexico, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Brazil, Honduras and Peru participate, among others. It has been held every year since 1960. In 2017, it was carried out on the Ancón military base in Peru, with participation by 17 countries and included exercises in military war scenarios by air, land and sea and in cyberspace. The different fleets were trained in naval operations combined with the “fight against organized crime,” the “digital war,” and air, amphibious and communications operations. Vice Admiral Manuel Vascones Morey, of the Peruvian Navy, said that the objective was to train the military forces “to be able to combat any common threat in our countries, such as drug trafficking, contraband, pirating; the type of scourges we currently have.”

• The PANAMAX exercise is an annual program organized by the Southern Command focused on training for possible conflict scenarios around the Panama Canal, especially terrorism, but also illegal substance trafficking and natural disasters. It has land, maritime, air and special forces components. It began in 2003 with participation by the United States, Panama and Chile. In 2016 and 2017, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Peru had crucial roles, either because it was their first time participating or they led or carried out some aspect of its components. These new roles were highlighted by the United States as a significant achievement.

• Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) is one of the biggest maritime exercises in the world. It is organized biannually off the coast of Hawaii. Begun in 1971 with the objective of impeding Soviet bloc expansion, only four countries participated. Today it is aimed at training the armed forces of 20 countries in a wide array of security situations, including the trafficking of goods and persons, and operations to counter the proliferation of arms of mass destruction. In 2018, it was led by Chile, marking the first time in the history of this exercise that a Spanish-speaking country was in charge of the training. Brazil participated for the first time in RIMPAC.

Latin American countries are assuming a greater leadership role in these exercises, promoting the involvement and training of their armed forces in security tasks. There is little information in general on the specific content of these events, other than what the states themselves make public.

Arms and equipment

The United States and other countries have sold equipment and weapons to Latin America to supply its military and police forces. In the majority of cases, the purchase and sale is justified in the name of “combating” drug trafficking and other forms of crime. Between 2000 and 2016, the countries of Latin America spent nearly US$9 billion on purchases of this kind from the United States. The biggest buyers were Colombia and Mexico, and to a lesser extent Brazil and Chile.

• Mexico. During 2015, the State Department approved the purchase of three Blackhawk helicopters, used by the US Army in Iraq and Afghanistan, to support the Mexican military. Another 18 helicopters of the same model equipped with GPS and machine guns had been acquired in 2014. In the official communication from the Defense Security Cooperation Agency, an agency of the Department of Defense, this transaction was justified as a contribution to the security of a strategic ally in the “combating of organized crime and drug trafficking.” In May 2015, these helicopters were used in a federal police operation that left 42 civilians dead in Michoacán.

• Peru. The modernization of its armed forces in 2011 sought to “improve the efforts of Peru in interdiction operations, its capacities for executing anti-narcotics and anti-terrorism operations, and to ensure the maintenance of border security.” In 2016, the United States sold infantry vehicles, machine guns and grenade-launchers to Peru, because “it is in the interest of US national security for Peru to provide its security forces with multipurpose equipment for border security, disaster response and to confront destabilizing internal threats, such as the Shining Path terrorist group.”

• Brazil. In 2014, Brazil acquired 20 Harpoon Block II missiles for its armed forces to use “for the purpose of encouraging its efforts to counter transnational organized crime.” That same year, it also bought Blackhawk helicopters. In June 2018, seven people died as the result of an operation led by the Civil Police in the Complexo da Maré, where a helicopter belonging to that force fl ew over the favela and fired from above into the population.

The United States is not the only country providing arms to the region. According to its latest arms exports report, the European Union issued licenses for arms sales in 2015 of some 5.89 billion euros to Brazil, 2.75 billion to Mexico, 1.14 billion to Peru, 478 million to Colombia, 440 million to Argentina, and 13 million to the countries of the Northern Triangle. Israel, Russia and Taiwan also traded arms and equipment with the region. In the case of Argentina, following an official visit by its security minister to Israel in 2017, the country acquired four Shaldag vessels and surveillance systems for land-border crossings for more than US$80 million. The equipment is supposedly for fl uvial border patrol and potentially for anti-narcotics operations. However, these are vessels of war. Israel, for example, uses them in combat zones like the Gaza Strip. Their use in places where there is no conflict of this type, such as the shores of the Paraná River, puts populations residing in these areas at risk. In October 2017, Argentina purchased four Texan II aircraft for the “logistical support” that the Air Force provides to border security forces in the northern part of the country to “combat drug trafficking.”

Military equipment purchases in the context of these measures against “new threats,” especially in the case of drug trafficking, run the risk of worsening social and institutional violence. First, the acquisition of this equipment by historically violent police forces increases the use of lethal force and risks of police executions and abuses. Moreover, this is a flow of potentially highly violent arms coming into a region with a significant illegal market. This proliferation of weapons translates into one of the highest firearm homicide rates, surpassing the world average. Illegal arms trafficking in border zones —for instance in the Tri-Border Area between Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil, or among the countries of the Northern Triangle—is just one of the problems. There is a huge quantity of arms that, once they come into the country through legal channels, are easily filtered into illegal markets.

Recent regulatory reforms

The armed forces in Latin America intervened in security matters for many years, and in many cases they still hold political weight. In various countries, they maintained internal security functions after the restoration of democracy. In the Southern Cone, after the civil-military dictatorships there, this role was more minor than in other countries. This may be attributed to the unique characteristics of those dictatorships and especially to how the subsequent transitions to democracy played out in these countries. For instance, more than a decade ago, the countries of the Andean region upheld that the armed forces played a very important role in the “war on drugs,” while in the Southern Cone it was sustained that this task lay with the police. This scenario began to change, however, in conjunction with the realignment of various countries with the “new threats” agenda. Thus, in 2012, more than 20 nations in the region declared to the Organization of American States that they regularly engaged their armed forces in security activities, using different procedures.

Most Latin American countries do not establish a clear division between security and defense functions in their legal framework.

Armed forces intervention in internal security permitted by Constitutions

Brazil and Colombia. The national Constitutions of Brazil and Colombia establish that the armed forces are for the purpose of “homeland defense” but also incorporate maintaining the public order and guaranteeing law and order among their missions. In both cases, they stipulate that the country’s president holds the power to use the armed forces during a set timeframe if public security were to be compromised and the capacities of the civilian forces exceeded. In Brazil, this legal framework enabled military intervention in the state of Rio de Janeiro in February 2018.

Peru and Bolivia. The Constitutions of these countries allow military intervention in the social and economic development of the country. This definition authorizes the involvement of the military in the operational functions of security, either temporarily or permanently, if the tasks are framed within attacks on national security or sovereignty.

Guatemala. Its Political Constitution states that the Army’s functions include maintaining “internal and external security.”

Honduras. Its Constitution specifi es that the armed forces “shall provide logistical support of technical advice in communications and transportation in the fight against drug trafficking” and “shall cooperate with public security institutions, at the request of the Secretariat of Security, to combat terrorism, arms trafficking and organized crime,” among other functions.

Armed forces intervention in internal security permitted by legislation

Ecuador and Venezuela. In Ecuador, the armed forces have the fundamental mission of “defending sovereignty and territorial integrity,” but the Organic Law of National Defense establishes that they may collaborate “on the economic and social development of the country.” Something similar occurs in Venezuela, where under its organic law, one of the armed forces’ missions is “cooperation in maintaining internal order and active participation in national development.”

Mexico. The organic laws governing its armed forces stipulate that its missions include “guaranteeing internal security and external defense” and “undertaking civic actions and social works aimed at the country’s progress; and in the case of disaster, helping maintain public order.”

Paraguay. The armed forces may be called upon to undertake security tasks when ordered by a Crisis Committee or in the face of situations in which police capabilities prove inadequate, as provided under its Law of National Defense and Internal Security.

Countries with a clear distinction between security and defense

Argentina, Chile and Uruguay have a clear distinction between the functions of internal security performed by the police and other security forces, and those of national defense in the hands of the armed forces. This demarcation is laid out in the regulatory plexus of these three countries, with some exceptions provided by law and by the express authority of the presidency in specific cases of crisis or national upheaval.

The United States

Within its national territory, the United States sustains a strict separation between the functions of the police and the armed forces. This principle does not arise from the Constitution but is enshrined in the Posse Comitatus Act, in force since 1878. This law, conceived to prevent the interference of the military in political-electoral affairs and in the repression of protests, has remained largely unchanged ever since. Its text provides for exceptional cases in which, with the authorization of the president or Congress, the armed forces could be deployed for internal use. Since the beginning of the 1990s, the military can participate in anti-narcotics operations to carry out activities of detection and monitoring, but not in seizures or detentions.

The division between military and police powers is rooted in US political culture, and attempts to substantially modify the law have not won consensus. As is evident, this is in contrast to its foreign policy whereby the country promotes strategies that would be prohibited in its own territory.

Based on these diverse regulatory structures, the militarization of security over the past two decades has produced significant changes in local laws and institutions. This phenomenon is manifested in a variety of ways:

• Regulations have been adopted permitting the shooting down of aircraft suspected of having ties to illegal drug trafficking. This has occurred in Colombia, Peru, Brazil, Bolivia, Venezuela, Honduras, Paraguay and Argentina. The armed forces are in charge of shooting them down, since any aircraft determined to be “hostile” is considered an attack on national sovereignty.

• Anti-terrorism laws have been passed throughout the region.

• Regulations have been created to authorize greater involvement of the armed forces in security tasks along with others that increase impunity for human rights violations committed by the military and police in the pursuit of crime.

The consequences of these reforms are vast. For example, according to specialists, after decades of these policies in Mexico and Colombia, three outcomes can be seen: “the restriction of fundamental rights; the militarization of public authority; [and] the emergence and consolidation of the exception in criminal justice.”

In parallel to these reforms, ambiguities are also exploited—through legal loopholes and other informal mechanisms—so that the armed forces can carry out tasks that, by law, are under the purview of the police or other agencies. In general, this is achieved by giving them a complementary role to the one played by the security forces. In El Salvador, for instance, eight decrees were issued between October 2009 and March 2014, authorizing the participation of military agents in different tasks and functions related to public security. This militarization by decree, which led to an unprecedented increase of soldiers on security detail and an expansion of the armed forces’ authority in this setting, was justified in the context of increased crime .

Various countries in the region are introducing reforms to their current regulatory frameworks regarding the functions of the military forces and their accountability within the scope of these functions, both new and old. At the same time, many countries have ongoing situations of military deployment that national laws only allow as an exception.

In other words, there is a clear tendency in the region to legally guarantee the enabling conditions for and continued use of the military as an instrument to address security problems or other social phenomena. This trend has rapidly grown over the last decade.

Laws and regulations that permit shooting down planes

In Brazil, the Lei do Abate was passed in 1998 and its detailed regulations issued in 2004. This law provides for the possibility of firing at aircraft “in clandestine flights” without approved fl ight routes and which are linked to illegal drug trafficking, including any proceeding from areas of drug production or supply, any following routes typically used by drug traffi ckers, or that omit information or refuse to respond to requests from the control tower.

Venezuela (2012)The Integral Airspace Defense Law was passed in 2012 by the National Assembly and regulated in 2013. It was conceived as one more element in the “fight against drug trafficking” and has been invoked on various occasions against aircraft suspected of transporting drugs. Venezuela is one of the countries in the region that has used its law on downing planes the most.

Bolivia (2014)Law 521 on the Security and Defense of Bolivian Airspace established “the procedures for interdiction of civil aircraft and the use of force against aircraft declared in violation, illegal or hostile” for the purpose of “identification, providing aid, requiring it to return to its route or to land.” The law stipulates that any physical aggression against aircraft in these circumstances is deemed rightful in legitimate defense of the state.

Peru (2015)Law 30.339 on Control, Surveillance and Defense of National Airspace authorizes the downing of “hostile” aircraft suspected of transporting illegal items (drugs, arms, explosives) and any that disobey military orders. Peru previously had a similar law in force between 1990 and 2001, which was suspended after the death of a woman and her seven-month-old baby when their plane was mistakenly shot down.

Argentina (2016)Decree 228/2016 declared a Public Security Emergency for a year, establishing the Rules of Airspace Protection and stipulating that, for the purpose of “reverting the situation of collective danger created by complex crime and organized crime,” the Air Force is empowered to intercept aircraft when they are suspected of transporting illegal substances and, if necessary, to employ firepower to take them down. This regulation was extended in January 2017 for another year.

Mexico’s Internal Security Law

For years, the growing military presence on the streets of Mexico developed without a specific legal framework to regulate the internal security tasks performed by the armed forces. In 2017, the government of Enrique Peña Nieto promoted an Internal Security Law that was passed by Congress, despite widespread opposition from an array of civil society sectors.

The law stated that “the armed forces may intervene in threats to internal security when the latter compromise or exceed the capacities of the authorities, and when there are threats arising from a lack of or inadequate collaboration by entities and municipalities in the preservation of national security.” The law thus legalizes a situation that had been the exception until then: military intervention in tasks traditionally reserved for the police. The ambiguous wording was criticized as enabling arbitrary application of the law.

The negative consequences of this law include the growing de-professionalization of the police, the expansion of intelligence tasks carried out by the military without public oversight mechanisms, increased violence, lack of accountability for actions by the armed forces, the expansion of military jurisdiction over civil legal matters upon giving the armed forces the power to participate in civil criminal investigations, the insuffi cient regulation of the use of force, and an imbalance in civil-military relations.

In July 2018, Andrés Manuel López Obrador won the presidential election with more than 50% of the vote. During the campaign, Alfonso Durazo, nominated for secretary of security, assured that López Obrador would not order the immediate withdrawal of the military from security duties but would do so gradually. After winning the election, more than 300 social organizations asked the future president to repeal the law. The incoming government sustained that it would await a Supreme Court ruling on claims of unconstitutionality. The interior minister, Olga Sánchez Cordero, affi rmed that the government will implement a peace strategy in conjunction with the United Nations and will seek to decriminalize the cultivation of marijuana and poppies.

Anti-terrorism laws and the construction of internal enemies

Hand in hand with the “new threats” paradigm and international pressure to join the “fight against terrorism,” many countries of the region in recent years have passed or amended anti-terrorism laws. Some of them, like Chile and Peru, already had legislation on this matter, but in most cases the laws and reforms occurred from 2010 onward. Some countries that passed or amended anti-terror legislation in this period are:

| Chile | Law 18.314 from1984, last amended in 2015 |

|---|---|

| El Salvador | Legislative Decree 108 from 2006 |

| Paraguay | Law 4.024 from 2010 |

| Argentina | Law 26.734 from 2011 |

| Venezuela | Published in Official Bulletin No. 39.912 from 2012 |

| Mexico | Reform of Federal Code in 2014 |

| Ecuador | Entry into force of Comprehensive Organic Criminal Code in 2014 |

| Brazil | Law 13.260 from 2016 |

| Honduras | Reform of Criminal Code in 2017 |

These laws may entail limitations on the exercise of the right to protest, freedom of association and expression, among other civil and political rights. The ambiguity of the criminal offenses included in them enables their use for criminalizing social conflicts. For instance, the Paraguayan law criminalizes as terrorist acts any efforts intended to “obligate or coerce (...) constitutional bodies or their members to act or to abstain from doing so in the exercise of their duties.” These definitions can be applied to social protests. One of the most worrisome aspects of these regulations is that they distinguish between legal and illegal protests, and authorize repressive state intervention when demonstrations do not comply with established criteria. Sometimes this occurs explicitly, because the law authorizes such repression, while in other cases it happens indirectly.

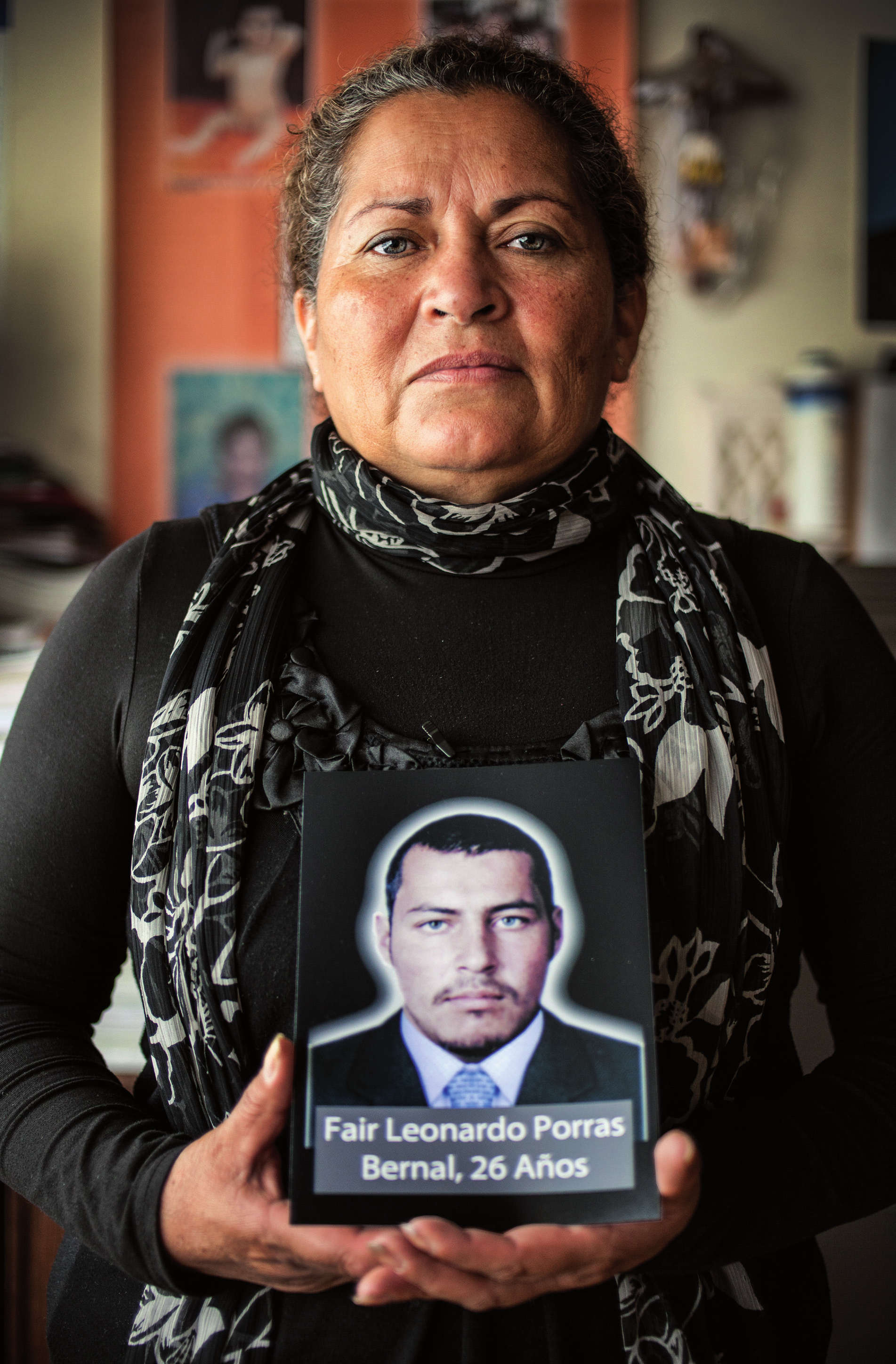

Anti-terrorism legislation is invoked in some countries to criminalize members of indigenous peoples, like the Mapuche in Chile and Argentina, and rural communities in Colombia and Peru. Something similar occurs in Central America with members of gangs or maras. The vagueness of anti-terrorism legislation has permitted its discretionary application against members of these groups, whom it labels as dangerous. In a number of countries, this has led to selective police practices, greater levels of institutional violence, and illegal intelligence practices and surveillance aimed specifically at these groups. These regulations overlap with the fact that military and police forces and other public officials depict them as “enemies” of state security or national sovereignty. Thus, state interventions and security policies against them are framed in terms of “war” and authorize the use of military techniques, resources, equipment and personnel for “combat” purposes.

Regulations expanding the powers of the armed forces

Regulatory reforms have often involved reducing legal restrictions on police and armed forces’ activities.

Peru: Law 30.151 from 2014 modified the Criminal Code by exempting from all criminal liability any armed forces or police officials who, “cause injury or death in carrying out their duty and using their weapons or other means of defense.” In practice, this legalizes extrajudicial killings.

Honduras: Crimes committed in the line of duty by the Military Police for Public Order, created in 2013, can only be investigated by prosecutors and tried by judges assigned by the National Council of Defense and Security, a body under the purview of the armed forces.

Colombia: In 2013, Law 1689 was passed creating the System of Technical and Specialized Defense of Members of the Public Forces. This system guarantees and fi nances the legal representation of police and military, on duty and retired, who are being tried in disciplinary proceedings or ordinary criminal proceedings. In 2015, Colombia’s Congress passed Law 1765 expanding the scope of the military justice system. Under that law, crimes such as homicide committed by police or the military, when considered related to the line of duty, will be tried by military justice.

Mexico: In 2008, the government of Felipe Calderón initiated a special criminal justice regime for offenses committed in the “organized crime” modality, restricting the rights of anyone charged with this type of crime. These changes were incorporated at the constitutional level and led to a series of reforms that criminalized diverse forms of collective action, accentuated discretionary action by police, and increased impunity in cases of human rights violations committed by members of the military and police.

Operational deployment of the armed forces in security tasks

The deployment of the armed forces in operational tasks to “fight crime” is a critical aspect for analyzing the evolution of militarization processes in Latin America.

Mexico is perhaps the most extreme case. In the context of an armed approach to drug trafficking, the military is currently carrying out detentions, patrols, inspections, raids and seizures in 27 states in the country, or three-quarters of Mexican territory. Between September 2016 and June 2017, on record there were 182 operations bases with 4,706 military troops assigned to public security tasks, with support from 468 vehicles. This represents an increase of 150% in fi ve years. The budget allotted to the Secretariat of the Navy (SEMAR) and the Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA) has doubled in the last ten years. In its 2015-2016 report, SEDENA informed having detained 3,808 persons in “operations to reduce violence indicators” and eradicated 7,500 hectares of marijuana crops and 35,000 of poppy. The anti-narcotics operations it participates in also grew exponentially.

In Colombia, the “counter-insurgency” agenda aimed at the armed groups leading the internal conflict explicitly overlaps with the anti-narcotics agenda. In a context that remains uncertain with regard to implementation of the peace agreements, some research contends that the armed forces not only will not be reduced in size or equipment, despite the fact that their growth was justified in response to that of armed groups, but that their tasks could possibly be expanded. For instance, they may be tasked with carrying out peace missions or providing training in other countries. The military was left in charge of safeguarding the areas of FARC influence during the demobilization process, especially in rural areas with low police presence. However, episodes of violence by paramilitary groups continue to occur.

Similarly, in Peru, the river valley area of Apurímac, Ene and Mantero (known as VRAEM) is still occupied by the military. In October 2016, former Peruvian President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski gave the armed forces principal jurisdictional authority in that area, declared an “emergency zone.” He appointed an Army general to lead the VRAEM Special Command, and a Navy admiral to lead the VRAEM Joint Special Operations and Operational Intelligence Command (CIOEC), to jointly carry out land, air and river operations. The former stated that Army members were “proud to be the strong arm of the state in its comprehensive fight against terrorism and drug trafficking in this part of the country.” The Peruvian government has justified its activities in the VRAEM as “anti-narcoterrorist” operations.

In addition to direct interventions via the military occupation of territories, the armed forces perform internal security actions in coordination with police institutions or other civilian agencies. In countries where this is more established as public policy, such as the Northern Triangle, there is evidence that military intervention has become more institutionalized through the creation of specific programs and special bodies made up of civilian and military personnel. In Guatemala, the Law on Support for Civilian Security Forces prevails, which stipulates that civilian police can also be “supported in their duties to combat organized and common crime by units of the Guatemalan Army, as deemed necessary.” There are also various inter-agency task forces on the borders with Mexico (Tecún Umán Inter-Agency Task Force), with Honduras (Maya Chortí Inter-Agency Task Force) and with El Salvador (Xinca Inter-Agency Task Force). These forces were established between 2013 and 2016 to confi scate illegal drugs in border zones and combat other forms of organized crime, and they joined forces with the Kaminal Task Force created in 2012, combining police and military personnel for patrol work in public spaces. Many of these forces are composed of members of the Army, National Police and Attorney General’s Office as well as personnel from Customs and Migrations. Its members were trained by the US Army.