Operation Condor

A criminal conspiracy to forcibly disappear people

CREDITS

research, writing and editing

Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales - CELS

images

León Ferrari

graphic design

Mariana Migueles

development

Clic Multimedia

coordinated repression

1

Operation Condor was a formal system to coordinate repression among the countries of the Southern Cone that operated from the mid-1970s until the early eighties. It aimed to persecute and eliminate political, social, trade-union and student activists from Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Paraguay, Bolivia and Brazil.

Operation Condor was officially founded on November 28, 1975 in Santiago, Chile during the closing session of the First Meeting of National Intelligence, and it was signed by intelligence representatives from Argentina (Jorge Casas, Navy captain, SIDE−the Argentine State Intelligence Secretariat), Bolivia (Carlos Mena, Army major), Chile (Manuel Contreras Sepúlveda, head of the DINA−the National Intelligence Office), Uruguay (José Fons, Army coronel) and Paraguay (Benito Guanes Serrano, Army coronel).

In Paraguay’s Archive of Terror, a copy was found of the formal invitation sent by the Chilean National Intelligence Office (DINA) on October 29 of that year to General Francisco Brites, Chief of the Paraguayan National Police, “to promote coordination and establish something similar to what Interpol has in Paris, but devoted to subversion.”

The founding document provided institutional coverage for many of the repressive intelligence activities, relationships and practices that these Latin American countries were already developing bilaterally. This document sets forth the beginning of official cooperation among the intelligence agencies of the Southern Cone: “as of this date, bilateral or multilateral contacts are hereby commenced at the will of the respective participating countries for the exchange of subversive information, the respective services opening their own or new background files.“ Although no representative of Brazil signed the inaugural agreement, that country’s cooperation in repressive activities against political opponents of the member countries has been proven.

Within the context of Operation Condor, the coordinated repression passed through different phases:

-In the first, a centralized database was created on guerrilla movements, left-wing parties and groups, trade unionists, religious groups, liberal politicians and supposed enemies of the authoritarian regimes involved in the operation.

-In the second, people considered political “enemies” at the regional level were identified and attacked.

-In the third and final phase, operations were carried out to track down and eliminate persons located in other countries in the Americas and Europe.

The declassified documentation available shows that various US government agencies had early knowledge of the scope of the repressive coordination and did not make much effort to stop it until it had reached the third phase, which proved the most problematic because the operations could no longer be kept under wraps.

Indeed, the detailed description of the different phases of Operation Condor and their scope are made abundantly clear in the analysis of the documentation declassified by the US State Department, which confirms that “’Operation Condor’ is the code name for the collection, exchange and storage of intelligence data concerning so-called ‘Leftists,’ Communists and Marxists, which was recently established between cooperating intelligence services in South America in order to eliminate Marxist terrorist activities in the area. In addition, ‘Operation Condor’ provides for joint operations against terrorist targets in member countries of ‘Operation Condor.’ Chile is the center for ‘Operation Condor’ and in addition to Chile its members include Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Brazil also has tentatively agreed to supply intelligence input for ‘Operation Condor.’ Members of ‘Operation Condor’ showing the most enthusiasm to date have been Argentina, Uruguay and Chile. The latter three countries have engaged in joint operations, primarily in Argentina, against the terrorist target.”

The document explains that this third, extremely secret, phase of Operation Condor “involves the formation of special teams from member countries who are to travel anywhere in the world to non-member countries to carry out sanctions up to assassination against terrorists or supporters of terrorist organizations from ‘Operation Condor’ member countries. For example, should a terrorist or a supporter of a terrorist organization from a member country of ‘Operation Condor’ be located in a European country, a special team from ‘Operation Condor’ would be dispatched to locate and surveil the target. When the location and surveillance operation has terminated, a second team from ‘Operation Condor’ would be dispatched to carry out the actual sanction against the target. Special teams would be issued false documentation from member countries of ‘Operation Condor’ and may be composed exclusively of individuals from one member nation of ‘Operation Condor’ or may be composed of a mixed group from various ‘Operation Condor’ member nations. (The) European countries specifically mentioned for possible operations under the third phase of ‘Operation Condor’ were France and Portugal.”

US reticence with regard to this final phase should not cause us to lose sight of the fundamental role the US played in the consolidation of the previous phases. Operation Condor ultimately had a computerized databank with information on thousands of individuals considered to be politically suspect, as well as photo archives, microfiches, surveillance reports, psychological profiles, reports on organization memberships, personal and political histories, lists of family members and friends. The computers for storing all this information were provided by the CIA, since no other country on the continent at that time had the sufficient technological means to do so. In addition, the member countries had at their disposal a protected communications system known as Condortel, the main base of which was located at a US facility on the Panama Canal.

orletti II

3

During the trial, the Federal Criminal Tribunal No. 1 took up case No. 1976 brought against “Furci, Miguel Ángel for aggravated deprivation of liberty and torture”, known as Automotores Orletti II.

Because of the links between what occurred at Automotores Orletti − the main concentration camp used to detain Operation Condor victims in Argentina − and Operation Condor itself, the court ruled that the trial would encompass all four cases: Condor I, II, and III and Orletti II.

In a few cases, the Orletti and Condor victims are the same.

Click on the red icon for more information.

some of the stories told during the trial

4

by Luciana Radó

a CELS intern who wrote the stories of the people made victims of Operation Condor, whose relatives we represented in the trial.CELS is part of the unified legal team representing plaintiffs along with Equipo Jurídico Kaos, Fundación Liga Argentina por los Derechos Humanos and attorney Alcira Ríos. We also represent the family members of Horacio Campiglia, Mónica Pinus de Binstock and Norberto Habegger, disappeared in Brazil, and Marcelo Gelman and María Claudia García Irureta Goyena, disappeared in Argentina and Uruguay, as well as the relatives of Uruguayan national Bernardo Arnone, disappeared in Argentina. Previously we represented the family members of María Emilia Islas Gatti and Juan Pablo Recagno Ibarburu, who died as the judicial process advanced.

- . Mónica Pinus de Binstock and Horacio Campiglia

Mónica and Horacio traveled on March 8, 1980 from Mexico to Rio de Janeiro. They had layovers in Panama and then in Caracas, where they boarded a Varig Airlines flight. Mónica was traveling under the name María Cristina Aguirre de Prinssot, and Horacio as Jorge Piñero. They were on their way to meet Edgardo Binstock, Mónica’s husband, who had arrived just days before. They were in the process of organizing a return to Argentina for the second counteroffensive by the Montoneros armed political group.

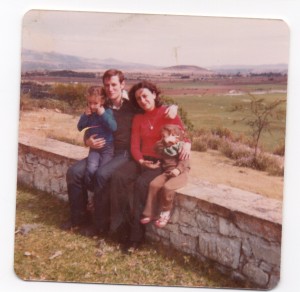

Mónica and Edgardo Binstock met in 1971, were married in 1974 and had two children, a daughter and a son. They were both sociology students at the University of Buenos Aires and activists in the Juventud Peronista (Peronist Youth) movement.

The judicial case incorporated two Brazilian news articles − taken from the book Fuimos Soldados, by Marcelo Larraquy − that pinpoint the moment of capture: “On the runway, soldiers speaking Portuguese set up an isolation cordon and separated the Montoneros from the other passengers, and both Pinus and Campiglia yelled out their identities and denounced that they were being kidnapped.” After being abducted from the Galeao Airport by members of the Argentine security and armed forces, with support from the Brazilian armed forces, they were transferred to Argentina and taken to the Campo de Mayo military base.

Army officer Cristino Nicolaides made public statements about an operation that could have been the one targeting Mónica and Horacio. Edgardo Binstock wrote him a letter in July 1981: “My wife and her travel companion were supposed to have met with comrades, all of whom are currently disappeared. Coincidentally (or not), your description leads me to believe that these are the very same people.” He later points out, “As her husband and on behalf of my two children, who, like many Argentine children, are growing up without knowing what happened to their mother, I demand that you make known the names of the detainees, what crimes they stand accused of, before what court the accusations were brought and where they are being tried. If not, you will be held responsible for all their lives. Simple as that.”

After the statements made by Nicolaides, a collective habeas corpus was filed on February 7, 1983 on behalf of numerous disappeared persons, which included Mónica Susana Pinus de Binstock and Horacio Campiglia. Horacio was married to Pilar Calveiro and had two daughters.

- . Norberto Habegger

Norberto Habegger was secretary of the political arm of the Montoneros. On July 31, 1978, he traveled from Mexico to Rio de Janeiro under the name Héctor Estaban Cuello to meet with other members of that organization. But between August 1 and 6, he was abducted, possibly by agents of the Argentine Federal Police, acting jointly with Brazilian security and armed forces. He was later presumably brought to Argentina.

After Norberto’s abduction, the intelligence agencies focused on following the actions taken by his family and by human rights organizations in their efforts to condemn what had occurred. A document dated January 11, 1980, entitled “Montonero’s campaign against Brazil,” indicated that Habegger’s wife, Florinda Castro, “was acting jointly with international and national organizations to denounce her husband’s disappearance.”

Habegger was assistant director of the newspaper Noticias at the time of the Argentine coup in 1976. He was a journalist for the magazines Primera Plana and Panorama, and also wrote the books Camilo Torres, el cura guerrillero, Los católicos post-conciliares en la Argentina and La huelga en El Chocón. Part of his political activity included a leadership role in the Christian Democratic Youth, and he later joined the Peronist movement. He belonged to the Argentine General Confederation of Labor (CGT in Spanish), and during the dictatorship from 1966 to 1973 he was a banking trade union leader. At the time of his abduction, he was 37 years old and father to a son, Andrés Camilo, who is now a filmmaker.

- . María Claudia García Irureta Goyena and Marcelo Gelman

María Claudia was kidnapped on August 24, 1976 in the city of Buenos Aires. A so-called task force team forced entry into the apartment where she lived with her husband, Marcelo Ariel Gelman. They were taken to the Automotores Orletti clandestine detention center, where both were tortured.

María Claudia was kidnapped on August 24, 1976 in the city of Buenos Aires. A so-called task force team forced entry into the apartment where she lived with her husband, Marcelo Ariel Gelman. They were taken to the Automotores Orletti clandestine detention center, where both were tortured.Two months later, in October 1976, Marcelo was killed. An investigation by the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF in Spanish) allowed his remains to be recovered more than 13 years later, after being buried as a John Doe in the San Fernando cemetery.

A witness in the case, who was also abducted and later released during the month of October, declared that Claudia was more than six months pregnant and was last seen just before giving birth. The witness also said that in September of that same year, Marcelo had been transferred.

Captain José Ricardo Arab and Major Manuel Juan Cordero Piacentini took Claudia to an office of the Uruguayan Defense Information Service (SID in Spanish). This was the place where Uruguayan detainees were held after being transferred from Orletti on the first prisoner flight, which took place on July 24, 1976.

While in labor, Claudia was taken to the Military Hospital of Montevideo, where she gave birth between the end of October and the beginning of November 1976. She remained in captivity until December of that year. A former SID soldier, Julio César Barboza Pla, saw her before and after the delivery.

Other former detainees testified that the guards had said they needed “a mattress urgently for a pregnant woman, who was on an upper floor.” One day they heard on the radio that the presence of an “Oscar 5” was requested urgently, because a woman was about to give birth, and they also recalled that the staff asked the women in the place “to prepare a bottle.”

When they were kidnapped, María Claudia was 19 years old and Marcelo, 20. The Argentine poet Juan Gelman found his granddaughter, Macarena, in 2000.

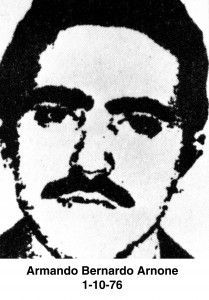

- . Bernardo Arnone

Bernardo was born in Montevideo on August 20, 1952. He lived in Piedras Blancas and was an activist in the Revolutionary Student Force (FER in Spanish) and the Workers’ Revolutionary Force (FRT in Spanish). He married María Cristina Mihura on July 25, 1974, and in June 1975 they moved to Buenos Aires, where he had a job at a metalworking company and joined the People’s Victory Party (PVP).

María Cristina testified at the trial that they left Uruguay after the coup d’état. Her mother-in-law, Petrona Hernández de Arnone, told her that while they were in Argentina, Uruguayan soldiers had gone to their house on several occasions asking about Bernardo. There were three of them, but she only recalled two names: Cordero and Gavazzo. In Buenos Aires, María Cristina lived in a number of boarding houses; Bernardo assumed another identity. He would spend two or three days with her and then leave.

Bernardo Arnone disappeared on October 1, 1976 in Buenos Aires. His mother, Petrona Hernández, remembers that the soldiers raided the family home on San Cono Street in Montevideo a few days after his disappearance, and dug holes all over the backyard in search of something they never found.

Bernardo and María Cristina were separated at the time of the abduction. She had begun a new relationship with Washington Domingo Queiró, who was disappeared on October 4 of that same year and never found since. She managed to get out of Argentina, flee to Sweden and save her own life.

- . María Emilia Islas Gatti and Jorge Zaffaroni

María Emilia was born in Montevideo on April 18, 1953. She and Jorge were student activists with the Association of Teaching Students in the Student Workers Resistance (ROE in Spanish), and they married in 1973. They had one daughter, Mariana. In 1975, they emigrated to Argentina for political reasons. In Buenos Aires, they participated in the formation of the People’s Victory Party (PVP).

María Emilia was born in Montevideo on April 18, 1953. She and Jorge were student activists with the Association of Teaching Students in the Student Workers Resistance (ROE in Spanish), and they married in 1973. They had one daughter, Mariana. In 1975, they emigrated to Argentina for political reasons. In Buenos Aires, they participated in the formation of the People’s Victory Party (PVP). On September 27, 1976, Jorge was kidnapped on the street by a group of people dressed as civilians, with no identification, who belonged to the Uruguayan Coordinating Body for Anti-subversive Operations (OCOA in Spanish). They took him to his home in Vicente López, where they stole everything of value while waiting for María Emilia and Mariana, who was 18 months old. They were all transported to the Automotores Orletti clandestine detention center located in the Flores neighborhood of Buenos Aires.

In 2003, the Uruguayan Peace Commission confirmed in its report that María Emilia “was probably transferred, with her final destination unknown, between October 5 and 6, 1976.” Mariana’s whereabouts came to light in 1983; she had been registered as the daughter of Argentine civilian intelligence agent Miguel Ángel Furci − indicted in this case − and his wife, Adriana González. In 1992, her true identity was restored and Furci was convicted for her appropriation in 1993. María Emilia and Jorge are still disappeared.

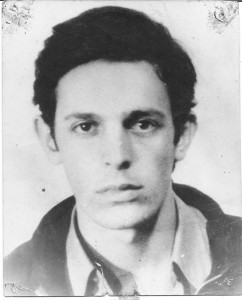

- . Juan Pablo Recagno Ibarburu

The Historical Investigation into Disappeared Detainees and Political Assassinations, presented on June 4, 2007 in Montevideo, revealed a secret document from 1976 from the Uruguayan Junta of Commanders-in-Chief, which gives an account of the procedures carried out in late 1976 against activists belonging to the People’s Victory Party (PVP).

The Historical Investigation into Disappeared Detainees and Political Assassinations, presented on June 4, 2007 in Montevideo, revealed a secret document from 1976 from the Uruguayan Junta of Commanders-in-Chief, which gives an account of the procedures carried out in late 1976 against activists belonging to the People’s Victory Party (PVP).The document indicated that the PVP “suffered, approximately three months ago, the loss of the majority of its best political cadres. Nevertheless, the military arm of the organization remained intact, not having lost a single man or any material resources. The military arm was located in the city of Buenos Aires.” This paragraph refers to the first group of PVP militant activists kidnapped between June 9 and July 14, 1976. All of those abducted were taken to Automotores Orletti, which was actively used as a secret detention center from May 11, 1976 through November of that year. On July 24, 1976, the kidnapping victims were transferred to Uruguay in a special flight (the “first flight”), ordered by the Defense Information Service and flown by Uruguayan Air Force pilots.

Between August and October 1976, 27 Uruguayan citizens were disappeared in Buenos Aires, which presumably culminated in their secret transfer during a “second flight” to Uruguay. This group of disappeared detainees included Juan Pablo Recagno Ibarburu, who had been abducted on October 2.

Juan Pablo’s nickname was El Colorado. He was a ceramicist and had worked as an illustrator in Buenos Aires for the Joker magazine between 1973 and 1976.

the right to truth

5

This trial brought to light very significant knowledge of Operation Condor as a criminal system, and that explains its importance in contributing to the truth. In addition, the judges have the opportunity to take up the demand for the right to truth regarding the events denounced by plaintiffs who have died over the course of this long judicial process. Reparation is thus a debt owed to their memory and to society as a whole.

With regard to the construction of knowledge, it must be stressed that hundreds of testimonies by people from all the Operation Condor member countries were given during the trial. The proceedings also included 12 reports from human rights organizations; six reports from international organizations; 423 files from the Argentine National Committee on the Disappearance of Persons, the Human Rights Secretariat and the Registry of Disappeared and Deceased Persons; 90 files and hundreds of documents from the Armed Forces and security forces; and eight documents from the Southern Cone Armed Forces.

Furthermore, tens of thousands of declassified documents from the US State Department were added to this material. In addition to the Chile Declassification Project, the requests from Argentine human rights organizations like Madres de Plaza de Mayo, Abuelas and CELS resulted in the Argentina Declassification Project being carried out in 2002, disclosing some 4600 documents. Reports from national and foreign archives were also incorporated into the case, such as those of the former Office of Police Intelligence for Buenos Aires Province (DIPBA in Spanish) and Paraguay’s Archive of Terror, as well as the evidence from 326 legal cases in Argentina and another 46 cases filed abroad.

With regard to recognition of the right to truth, while it was initially considered to be limited to victims and their families, over time it has come to be seen as a right that also belongs to society as a whole. This is how the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has interpreted it, in specifying that even in cases where amnesties are granted, States must adopt the necessary measures to establish the facts and identify those responsible, and that the entire society has the inalienable right to know the truth about what occurred as well as the reasons and circumstances in which the crimes were committed, thus reaffirming the collective nature of this right.

Over the course of these long proceedings, a number of the accused have died or been removed from the process. However, it is our view that the State has an obligation, stemming from cases of crimes against humanity, to investigate and publicly release those facts that can be reliably established, even when it is not possible to convict a responsible party. The unified legal team led by CELS solicited, on grounds of the right to truth, that the court deem the events that caused grave harm to Fausto Augusto Carrillo Rodríguez, Agustín Goiburú Giménez, Norberto Armando Habegger, Horacio Campiglia, Mónica Susana Pinus de Binstock, Luis Enrique Elgueta Díaz, Adalberto Soba Fernández, María Emilia Islas Gatti, Cecilia Susana Trías Hernández, Juan Pablo Recagno Ibarburu, Casimira María del Rosario Carretero Cárdenas, Rafael Laudelino Lezama González, Carlos Alfredo Rodríguez Mercader and Armando Bernardo Arnone Hernández to have been proven in their entirety.

the accused and the victims

6

Over the course of the hearings we were able to prove that the accused, all of them former military officials, were part of a criminal conspiracy dedicated to the enforced disappearance of 105 people, among other crimes, and that they were responsible for the illegal deprivations of liberty of which they were accused. These defendants were Humberto José Ramón Lobaiza, Felipe Jorge Alespeiti, Bernardo José Menéndez, Antonio Vañek, Eduardo Samuel Delío, Federico Antonio Minicucci, Néstor Horacio Falcón, Eugenio Guañabens Perelló, Carlos Humberto Caggiano Tedesco, Carlos Horacio Tragant, Juan Avelino Rodríguez, Santiago Omar Riveros, Reynaldo Benito Bignone, Luis Sadi Pepa, Rodolfo Emilio Feroglio, Enrique Braulio Olea and Manuel Juan Cordero Piacentini.

Finally, we proved that Miguel Ángel Furci was criminally responsible for the illegal deprivation of liberty of 67 people and the torture they suffered while in captivity at the Automotores Orletti Clandestine Detention Center.

the verdict

7

For the first time in history a court ruled that Operation Condor was a criminal conspiracy to forcibly disappear people across international borders. The Operation’s scope was proven in its full magnitude. For many reasons this trial had unique characteristics and was of great regional importance: due to the sheer number of evidentiary documents involved; the hundreds of testimonies given either in person or via videoconference from witnesses’ countries of residence; and the vast group of people who were the plan’s victims, which included political, social, trade-union and student activists of various nationalities. All of this made it possible to prove the existence of a formal system of repressive coordination between the dictatorships of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay.

In its verdict, Argentina’s Federal Tribunal No. 1 determined that the accused were part of that criminal system and were responsible for some specific Condor operations. For these reasons the court sentenced Santiago Omar Riveros and former Uruguayan military official Manuel Juan Cordero Piacentini to 25 years in prison. Reynaldo Benito Bignone and Rodolfo Emilio Feroglio to 20 years. Humberto José Ramón Lobaiza to 18 years. Antonio Vañek, Eugenio Guañabens Perelló and Enrique Braulio Olea to 13 years. Luis Sadi Pepa, Néstor Horacio Falcón, Eduardo Samuel Delío, Felipe Jorge Alespeiti and Carlos Humberto Caggiano Tedesco to 12 years. And Federico Antonio Minicucci was sentenced to 8 years in prison.

All of the accused belonged to Argentina’s military forces with the exception of Cordero, who was extradited from Brazil for this trial. He had never been convicted of a crime in his native Uruguay. Bignone was the last dictator of the military junta that ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1983, but his conviction in this trial refers to actions he took prior to assuming that post.

In addition, the court sentenced Miguel Ángel Furci, a former Argentine intelligence agent, to 25 years in prison for being co-perpetrator of the crime of illegal deprivation of liberty, aggravated by violence and threats, committed against 67 people during their captivity in the clandestine detention center known as Automotores Orletti.

Juan Avelino Rodríguez and Carlos Horacio Tragant were acquitted.

The verdict was handed down on May 27, 2016.