ESMA mega-case

The trial

CRÉDITOS

investigación, textos y edición

Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales – CELS

fotografías

CONADEP

videos

Memoria Abierta

diseño gráfico

Mariana Migueles

desarrollo

Clic Multimedia

The third trial

0

The crimes committed in the clandestine detention and torture center that functioned in the School of Naval Mechanics (Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada, ESMA) began to be prosecuted in two prior trials. The first one was carried out in December 2007, with only one defendant: Héctor Febrés. His death just days before the verdict was to be handed down put a stop to the trial. The second trial began in late 2009 with 86 cases, the investigation of which had been suspended due to the Full Stop and Due Obedience amnesty laws, passed in 1986 and 1987. In that instance, case 1270 (as it was known) centered on the period under the command of Jorge Eduardo Acosta’s Task Group until 1979, and it ended with 16 people convicted and two acquitted.

The trial that draws to a conclusion on November 29, 2017 is the largest in Argentine history. It investigated the crimes against humanity committed against 789 people, and the verdict will be heard by 54 defendants.

The Unified ESMA case or ESMA “Mega-case” allowed for unraveling the Navy’s repressive structure and identifying the stages of the criminal repression carried out at the ESMA, between 1976 and the end of the dictatorship in 1983. In this trial before Federal Criminal Tribunal N°5, solid evidence was arrived at thanks to analysis of the oral testimony provided and work on the archives of the Armed Forces and security forces – which were studied by teams at the Defense and Security Ministries and by the Foreign Ministry’s Committee for Historical Memory.

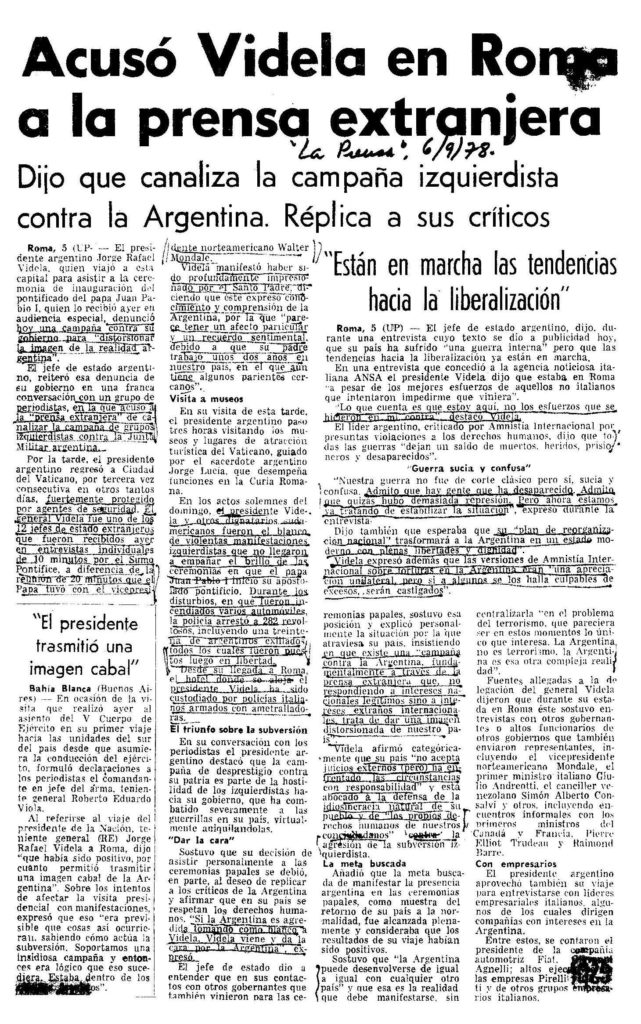

Over the course of the trial, attention was focused on the stage at which denouncements abroad of human rights violations in Argentina gained greater relevance. At that time, the dictatorship led a strategy to intervene in this “anti-Argentine” campaign via triangulated actions between the ESMA, the Foreign Ministry and the creation of the Pilot Center in Paris, which allowed for organizing the persecution of political opponents outside the country. In addition, the trial also served to reconstruct the so-called death flights (their structure and operational mode) and to deepen knowledge about how the ESMA functioned as a clandestine maternity ward. The role of the Catholic Church was also exposed in this trial with the transfer, for example, of “Silence” island so that in 1979, Task Group 3.3 could use it to hide ESMA’s disappeared detainees during the visit of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). The island was property of the Buenos Aires Archbishopric.

The novelties brought to light by this trial strengthen the articulation between justice and truth: today we know much more about the way ESMA functioned as a clandestine detention and torture center. The reparation of victims and of society is only possible if the state complies with its obligations to investigate, sanction and reconstruct history.

Death flights: The final solution

1

From the time of the dictatorship, there was knowledge that death flights were used as a system for physically eliminating people kidnapped by the state. In this trial, however, participants were able to reconstruct their specific technique, demonstrate what aircraft were used and identify the naval structures that provided the material and human resources for the flights.

The first references to the death flights were made by dictatorship survivors Sara Solarz de Osatinsky, Alicia Milia and Ana María Martí in the “Paris Testimony” of 1979, and by Horacio Maggio, who was able to escape the ESMA in 1978 and who pointed to the use of helicopters.

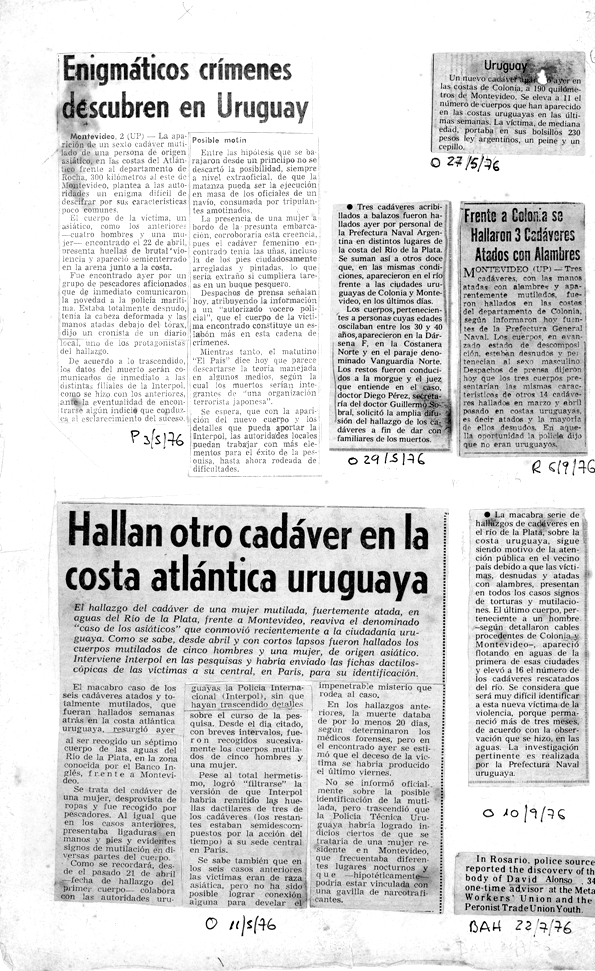

On Argentina’s coastline, several days after their abductions between December 8 and 10, 1977, the bodies of Azucena Villaflor de Devincenti, Esther Ballestrino de Careaga, María Ponce de Bianco, Ángela Aguad and the French nun Leonie Duquet appeared. Cadavers also surfaced on the beaches of nearby Uruguay.

The silence of the Church

2

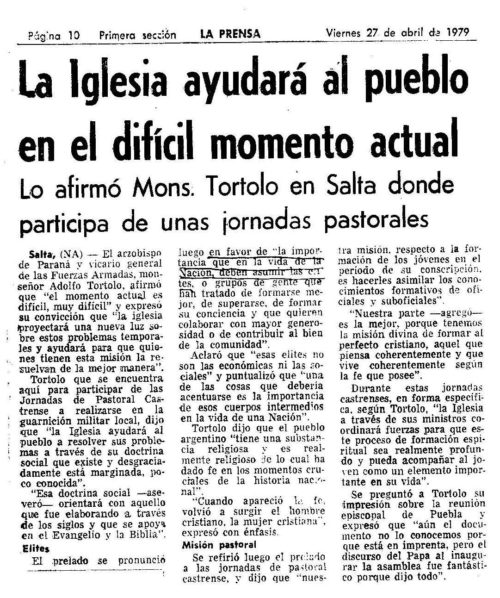

The responsibility held by the Catholic Church can be broken down into: its concealment of the crimes it knew were being committed; moral support provided to the high command; support for the ideological underpinnings of the dictatorship; supplying the Armed Forces with information obtained from families searching for the disappeared; consolation the chaplains gave to the torturers and pilots who threw people alive into the ocean: “I don’t know if it comforted me, but at least it made me feel better,” said naval officer Adolfo Scilingo.

The media

3

The same day of the coup (March 24, 1976), the military Junta’s Edict 19 imposed the reclusion for ten years of anyone who “by any means publishes, discloses or spreads news, communications or images for the purpose of disrupting, jeopardizing or discrediting the activity of the armed, security or police forces.”

Some media outlets played a complacent role with the civil-military dictatorship, while others identified with it ideologically. For instance, despite the reports that revealed or at least raised suspicions that the disappeared were being held at ESMA, and tortured and killed, the media published “official” versions of the events that made the deaths seem like confrontations. The Navy authorities, meanwhile, modified the structures and composition of the ESMA task force, among other reasons, to be able to send officers abroad to mitigate the consequences of the propaganda efforts to expose the crimes.

Some of the 789 stories

4

Among the cases that CELS represents are the kidnappings and disappearances of the villa del Bajo Flores group members, including Mónica Mignone, daughter of one of CELS’ founders. We also represent the families of Ariel Ferrari, Alcira Fidalgo, Sergio, Hugo and Betina Tarnopolsky, Blanca Edelberg, Laura Del Duca, Pablo Lepíscopo and Fernando Brodsky, Graciela García and Marta Álvarez; CELS also intervened in the trial as a human rights organization.

In addition, as part of a unified legal team, we made pleadings on behalf of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo Línea Fundadora, Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, Isabel Teresa Cerrutti (regarding her partner, Ernesto Berner), Marina Girondo, Victoria Grigera Dupuy and Ramón Camilo Juárez (members of H.I.J.O.S.), Javier Martín Juárez and the plaintiffs represented by lawyers Alcira Ríos and Pablo Llonto.

- I. Mónica Mignone and the villa del Bajo Flores group

“That morning, at 5 a.m., we heard the doorbell; it rang non-stop and we heard banging on the door. My parents woke up and went to the door. My father asked what was going on, to which they violently responded, shouting that they were from the Armed Forces. When my father asked to see some identification, they showed him a machine gun,” testified Mercedes Mignone. Her sister Mónica, 24, did volunteer work in the Bajo Flores villa (or shantytown), along with María Marta Vásquez Ocampo and several priests.

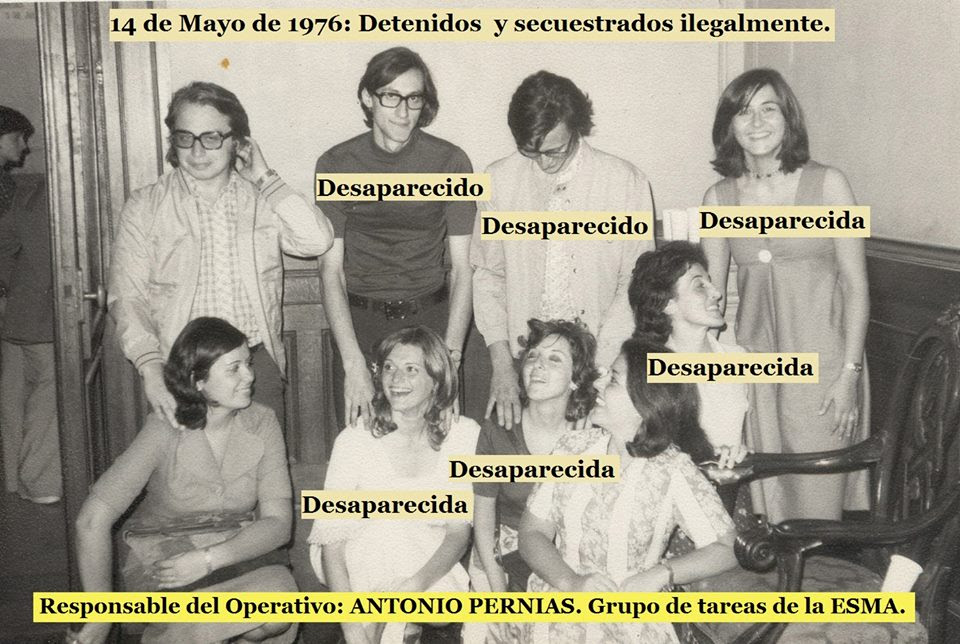

Mónica and María Marta were kidnapped on May 14, 1976. The operation targeted the entire group of friends who used Bajo Flores as the base for their political activism work for the Peronist villa movement.

Mónica and María Marta knew each other from school (Colegio de la Misericordia). Their friendship extended to their parents: Angélica Sosa de Mignone and Emilio Mignone (two of CELS’ founders), Marta Ocampo and José María Vásquez. The two young women met César Amado Lugones and Horacio Pérez Weiss when they went to teach catechism and do social work in the south of the country. María Marta and César began dating and Horacio married Beatriz Carbonell. Mónica Quinteiro, one of Mónica and María Marta’s teachers, was also part of the group, as was María Ester Lorusso.

They were all kidnapped and they remain disappeared to this day.

- II. Marta Álvarez: enslaved to work as a journalist

People called Marta Álvarez “Peti” (a term of endearment meaning petite or tiny in Spanish). She was a political activist in the Peronist Youth organization and a union delegate at the newspaper La Razón. She was kidnapped at dawn on June 26, 1976, from an apartment in Vicente López, along with her partner Adolfo Kilmann, Rita Irene Mignaco and Rita’s husband Javier Otero, who at the time doing military service at ESMA.

Marta was able to tell the court that she was taken to a place she later identified as the ESMA. As soon as she arrived, they took her to the basement to be interrogated. They stripped her, tied her to a mattress base and was tortured with an electric prod by Francis Whamond and Antonio Pernías, among others.

Marta said that after a while, Pernías left the torture room and, on returning, ordered that they stop torturing her because she was pregnant. They took her to a section known as “Capucha” (Hood). They left her there for several days handcuffed with shackles on her feet and a hood over her head.

- III. Graciela: living to tell the tale

Graciela García Romero was with Diana García, a colleague, in downtown Buenos Aires on the corner of Córdoba Avenue and San Martín on October 15, 1976, at three o’clock in the afternoon when they were kidnapped. Graciela was a political activist in the Montoneros organization and Diana was dating Miguel Coronato Paz, collaborator of ANCLA. They were taken to ESMA. Diana remains disappeared.

Graciela was tortured, subjected to a mock execution and detained under inhumane conditions. Pernías told her that they were looking for her and that they knew where she was working as a political activist.

Graciela was also sexually abused by Jorge Acosta. In January 1977, he took her twice to an apartment without electricity on Olleros and Libertador. Acosta carried bed sheets in a leather suitcase. After raping her, he took her back to the ESMA, shackling and handcuffing her to a partition.

- IV. Ariel Ferrari: targeted by Astiz

Ariel Ferrari, 25, a political activist in the Montoneros organization, went by the name Felipe. He was kidnapped on February 27, 1977 as he was leaving a friend’s home in Villa Devoto. He was badly injured in the process and he died on the way to the ESMA.

Other operations had been carried out in the home of Ariel’s relatives and at two of his former addresses. Given the threaten, the Ferrari family and Ariel’s girlfriend, Liliana Bietti, went into exile in Brazil. Ariel refused to meet up with them there, which he stated in several letters. In February 1977, all correspondence ceased. Then, in 1978, Ana Villa wrote to tell them that she had seen Ariel’s dead body in the ESMA.

- V. A decimated family: the Tarnopolskys

Almost the entire Tarnopolsky family was kidnapped by the ESMA Task Group. The only surviving family member, Daniel Tarnopolsky, told the court what happened.

Sergio Tarnopolsky, 21, was a psychology student doing his obligatory military service at the ESMA. On July 13, 1976, he was detained there, tortured and clandestinely held under inhumane conditions.

The night he was detained, Sergio was supposed to come home but he never did. The following day, July 14, he called his wife, Laura, on the telephone and told her he was going to stay on guard duty. Days later, Laura’s mother, Raquel Menéndez, went to the ESMA looking for information about Sergio’s whereabouts: they told her that they did not know where he was.

- VI. Franca Jarach: the future of unions

Franca Jarach was a passionate and very talented young woman who was very sensitive to injustice: that was how her mother, Vera, described her. She was a student at the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires, was active in the political organization of high school students Unión de Estudiantes Secundarios (UES), and later in the Peronist Working Youth.

She was kidnapped on June 25, 1976, along with Hernán Daniel Fernández. They were taken from a coffee shop on the corner of Carlos Pellegrini and Córdoba Avenue. Franca was taken to the ESMA. She was part of a “transfer” (a euphemism for murdering detainees) in July 1976.

- VII. Fernando Brodsky: pretend that I went traveling

Fernando Brodsky was kidnapped along with Juan Carlos Chiaravalle on August 14, 1979 from his home in Vicente López. Fernando, 22, was a university student and a preschool teacher. He was taken to the ESMA, where he was tortured. He was later part of a “transfer” (an operation to kill detainees).

- VIII. Pisco: the "transfers" of the Villaflor Group

Pablo, 24, was known as ‘Pisco,’ a nickname based on last name: Lepíscopo. He first began working as a political activist at the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires, as a member of the Frente de Lucha de Secundarios (FLS). He later joined the Peronismo de Base before he finally ended up in the Montoneros Villaflor Group, along with Fernando Brodsky.

On August 5, 1979, Pablo had lunch at his parents’ house. He left in the afternoon, and around 6 p.m. he was kidnapped. He was in his Renault 12 taxi, with his girlfriend, Bettina Ruth Ehrenhaus. The two were abducted by men in plain clothes. They beat them, put them in a vehicle and blindfolded them. Bettina was released two days later and she left the country. We know the facts thanks to her accounts.

- IX. Alcira Fidalgo: the bionic girl

She was a poet and an illustrator. She studied law at the UBA and was a member of the Peronist University Youth (JUP). Alcira Graciela Fidalgo was kidnapped on December 4, 1977, in front of a movie theater on Lavalle Street.

She was taken to the ESMA, where they tortured her. At first, she was kept in the sector known as “Capucha” and then it was taken to “Capuchita.” She was detained from late 1977 until early 1978. She is still disappeared.

The verdict

5

The court acquitted: Juan Alemann, Ricardo Jorge Lynch Jones, Roque Ángel Martello, Rubén Ricardo Ormello, Julio Alberto Poch and Emir Sisul Hess.

It convicted to life in prison: Jorge Eduardo Acosta, Randolfo Agusti Scacchi, Mario Daniel Arru, Alfredo I. Astiz, Juan Antonio Azic, Ricardo Miguel Cavallo, Daniel Néstor Cuomo, Rodolfo Cionchi, Alejandro Domingo D´Agostino, Hugo Enrique Damario, Francisco Di Paola, Adolfo Miguel Donda, Miguel Ángel García Velasco, Pablo E. García Velasco, Alberto E. González, Orlando González, Rogelio José Martínez Pizarro, Luis Ambrosio Navarro, Antonio Pernías, Claudio Orlando Pittana, Jorge Carlos Rádice, Francisco Lucio Rioja, Juan Carlos Rolón, Néstor O. Savio, Hugo Sifredi, Carlos Guillermo Suárez Mason, Gonzalo Torres de Tolosa, Eugenio Vilardo and Ernesto F. Weber.

25 years in prison: Juan Carlos Fotea

20 years in prison: Rubén Oscar Franco

17 years in prison: Eduardo Aroldo Otero

16 years in prison: Guillermo Pazos

15 years in prison: Carlos Octavio Capdevila

14 years in prison: Víctor Roberto Olivera and Jorge Luis Magnacco (in this last case the court merged this conviction with previous ones and imposed a sentence of 24 years in prison)

13 years in prison: Juan Arturo Alomar

12 years in prison: Carlos Eduardo Daviou and Jorge Manuel Díaz Smith

11 years in prison: Héctor Francisco Polchi

10 years in prison: Daniel Humberto Baucero and Antonio Rosario Pereyra

8.5 years in prison: Paulino Oscar Altamira

8 years in prison: Julio César Binotti, Miguel Enrique Clements, Juan de Dios Daer, Mario Pablo Palet and Miguel Ángel Alberto Rodríguez.

Closing remarks: Vera Jarach at the trial

6

We know that Truth, Justice and Memory are the best guarantees for “Nunca Más” (Never Again)… With our efforts to promote Memory, we try to ensure that these tragedies don’t fall into oblivion and, on the contrary, that they allow us to recognize symptoms of repetition… since history teaches us that what happened once, unfortunately, can happen again. My own life exemplifies this, with the analogies of two histories, that of my maternal grandfather, deported and killed in Auschwitz, and that of my daughter many years later, in the ESMA – two emblematic concentration camps, gas chambers and death flights, no graves, wounds that don’t heal, without any possibility of mourning. And there are many other similarities in the ferociousness and the will, not only to kill but also to erase any trace. They did not achieve this last thing and they will not achieve it as long as we live and the justice system fulfills its mission, leaving ethically indelible marks.