In an important ruling, the National Supreme Court of Justice (CSJN) recognized the critical overcrowding of the penitentiary system in the province of Buenos Aires and ordered the Provincial Supreme Court to deal with the structural violations of the rights of incarcerated persons. This problem is so severe that it requires substantive measures and coordinated action to ensure their effectiveness. The CSJN further ruled that detention in police establishments is inappropriate and that decommissioned sites not be reinstituted. The legal action had been submitted in 2014 by the Buenos Aires Provincial Defense Council, citing non-compliance with the Supreme Court’s Verbitsky ruling of 2005.

In that ruling, the Court issued guidelines for ceasing the rights violations caused by prison crowding; the province, however, has shown no signs of implementing them so far. In response to a habeas corpus filed by CELS in 2001, the CSJN had resolved that the situation in the provincial prison system was critical and required coordinated action among the three provincial state powers to ensure the protection of the prison population’s rights and guarantees. Among other concrete measures, the CSJN ordered the provincial high court and judges to ensure “the urgent cessation of the aggravation of the case, or the detention itself, accordingly.”

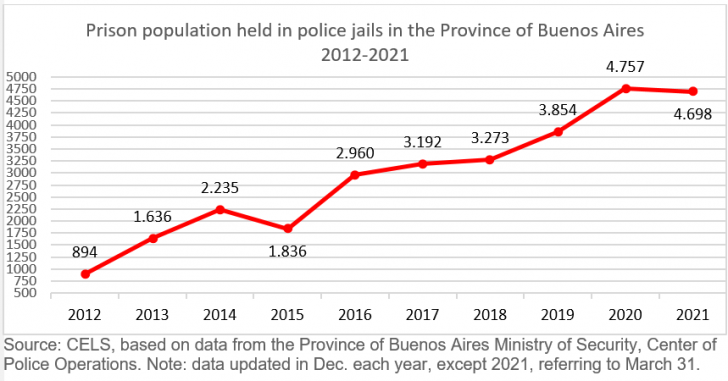

Aside from a few years of improvement immediately following that ruling, the situation deteriorated again. As of 2012, the total prison population went from 30,000 to nearly 50,000. As a result, cells at police stations became a place of permanent incarceration: the number of people held in police jails increased by 426% in that period, reaching a peak of 5,661 people by Nov. 2020. These numbers remain at an intolerable level today.

The backdrop to this exponential increase is a punitive criminal policy focused on the use of incarceration as the only response to a broad spectrum of problems ranging from violent crimes to social conflicts. Under the assumption that society demands that punitive response, the State reinforces this demand and promotes initiatives such as toughening up on preventive prison, incarceration for minor crimes or blocking the gradual implementation of the penalty. These measures have not had a positive impact on reducing the dynamics of violence, but instead have produced a humanitarian catastrophe in the province’s prison system.

Since 2012, CELS has insisted on multiple occasions that the humanitarian crisis in the provincial prisons must be dealt with comprehensively and structurally. Among other measures, we initiated two cautionary measures still in process with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. These instances generated spaces of dialogue with the different provincial governments in which we were able to establish a protocol for investigating cases of torture, and another on the rational use of force in penitentiary units. Nevertheless, the provincial government has thus far not taken measures to reduce crowding or stopped using police establishments – some of which were even decommissioned – as places for prolonged holding of detainees.

In 2020, once the pandemic started, we warned the Provincial Supreme Court (SCBA) about the need to adopt structural measures to prevent the collapse of its prison system in the event of a breakout of the virus inside prisons. The SCBA chose not to intervene.

Later, as an alternative strategy, we went before the Supreme Court in the context of the action brought by the Provincial Defense Council to reaffirm the need to discuss the non-compliance with the collective Verbitsky habeas corpus. It has been nearly seven years now that the Court should have ruled on that petition. The aggravation of the situation during the previous administration of María Eugenia Vidal in the province along with the health crisis brought by the pandemic have brought this unresolved case front and center once again.

Thus, this past May 14, after several years of accelerated growth in the incarceration rate in the province and deepening of the prison crisis, the CSJN finally ruled that the measures ordered in 2005 in the Verbitsky collective habeas corpus are in force and have not been complied with, and established explicitly that, for these reasons, the case is not closed. Based on this decision, the situation of persons deprived of liberty must be dealt with by the Provincial Supreme Court without alleging that this is about political matters in which the provincial justice system has no responsibility. The re-opening of this judicial instance must provide the framework for the discussion about effective measures jointly with the executive and legislative branches to lower the incarceration rate and resolve the prison crisis in the province.