The “2 for 1” law passed in 1994 was aimed at compensating people who were incarcerated for long periods under pretrial detention. It stated that any year spent in pretrial detention after the first two years should count doubly when calculating a final prison term, effectively reducing prison sentences. In May 2017, Argentina’s Supreme Court applied this benefit to Luis Muiña, who had perpetrated crimes against humanity – provoking a massive social and political mobilization in rejection of this new form of impunity.

However, in its recent ruling on the Batalla case, the Supreme Court determined that the “2 for 1” benefit is not applicable to people convicted of crimes against humanity. With this decision, the Court reestablishes a consolidated and homogenous position with regard to the judicial approach to state terrorism.

For the high court, “crimes against humanity express the most degraded state of human nature,” and for that reason the “2 for 1” benefit is inapplicable in these cases. The justices concur with the law passed almost unanimously by Congress, shortly after the Muiña ruling, in that these crimes are sufficient grounds for sustaining the inapplicability of the “2 for 1” benefit to their perpetrators. In this way, the Court reaffirmed the principles of the international human rights system.

The Batalla ruling refers back to decisions by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to base its findings on international standards for the investigation and possible sanction of those responsible for grave human rights violations. The Muiña ruling was incompatible with those standards. For that reason, different bodies of the universal and inter-American human rights protection systems interpreted it as a step backward in the Argentine process of justice, which they recognize as exemplary. Court justices Ricardo Lorenzetti and Juan Carlos Maqueda had already expressed that same line of thinking in their dissenting votes from 2017.

In response to the Muiña ruling, Argentine congresspeople from across the political spectrum approved Law 27.362, interpreting the scope of the “2 for 1” benefit and reaffirming what the international treaties signed by Argentina already established: that crimes against humanity cannot be subject to amnesties or pardons, nor can related prison sentences be commuted. The new ruling analyzes that law’s application to the case of Rufino Batalla. The Supreme Court argued that at the time Law 24.390 was passed, establishing the “2 for 1” benefit, the impunity laws known as Due Obedience and Final Stop were in force, halting the progress of the majority of judicial investigations into crimes against humanity. This situation only changed when the trials were reopened. According to the Supreme Court, this new legal paradigm made it necessary to recontextualize the interpretation of when to apply the benefit set forth in Law 24.390 – a task that corresponds to Congress, not the judicial branch.

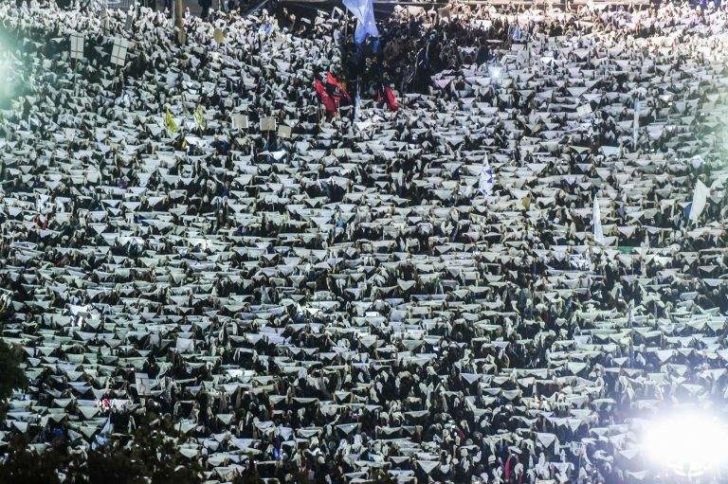

In 2017, the Muiña ruling represented the convergence of some government discourses relativizing state terrorism with a judicial decision. The continuity between such political positions and the Supreme Court ruling was grave and alarming. However, the social and political mobilization against it was massive and paved the way for this new milestone in the Argentine justice process.