Mercedes-Benz Argentina is a subsidiary of the German automotive company currently known as Daimler AG. Throughout its history, it obtained benefits from the state, such as those linked to investment promotion policies, tax breaks, export facilities and the state’s absorption of its debt during the last civic-military dictatorship. In 1979, it controlled 92% of the local market for buses.

During the 1970s, labor conflicts were on the rise within the company. Workers expressed demands regarding wages and improved working conditions, and they obtained some victories. However, with the coup of March 24, 1976, things changed. At least 20 Mercedes-Benz workers were the victims of crimes against humanity. Of those, 15 remain missing to this day. This repression had a profound impact in disciplining workers.

The trial that is now taking place –known as the Campo de Mayo mega-case– is divided into distinct segments. One of them is prosecuting the crimes committed against Mercedes-Benz workers who were detained illegally in the clandestine centers that functioned inside the Campo de Mayo military complex.

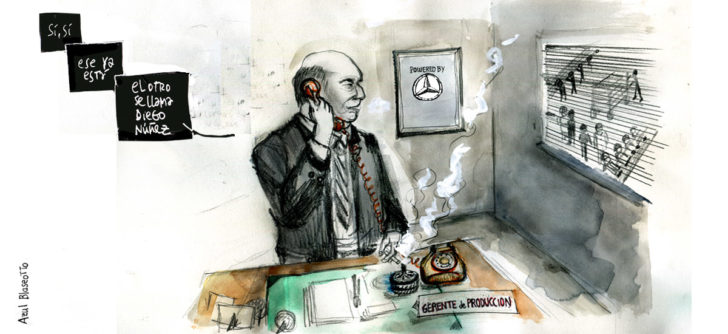

Between May 22 and June 19, witnesses testified before Federal Oral Criminal Court No.1 about the kidnappings and disappearances of seven workers between 1976 and 1978, of whom six remain disappeared: Alberto Francisco Arenas, Juan José Mosquera, Héctor Aníbal Ratto (survivor), Jorge Alberto Leichner Quilodran, Alberto Gigena, Diego Eustaquio Nuñez and Fernando Omar Del Contte. There is sufficient evidence that shows how company executives gave information about the workers to the dictatorship. The victims were not selected at random: they were all labor activists.

Testimony from May 22

Julio D´Alessandro, a former employee of the company, told the court how Mercedes-Benz executives hampered workers’ efforts to organize a union in diverse ways. He worked there from 1971 to 1975 and stayed in contact with many of his former co-workers who remained at the job, including Diego Eustaquio Nuñez, who was disappeared and is still missing. The difficulties they faced inside the company to assert their labor rights kept them from formally establishing the internal trade-union commission that they wanted and that had been elected by their colleagues. Many of them remain disappeared to this day. D´Alessandro explained that the primary production at that time was trucks that were sold to different Latin American dictatorships or earmarked for the Argentine Army. He also added that company executives were absolutely opposed to halting or slowing production. Eduardo Estivil Navarro, another former employee of Mercedes-Benz at that time, gave similar testimony.

Mirta Arenas, the sister of Francisco Alberto Arenas, and Silvia Graciela Núñez, the sister of Diego Eustaquio Núñez, testified about the circumstances of their brothers’ kidnapping and subsequent disappearance. Both men worked at the company at the time they were abducted. Francisco and Diego were friends and actively participated in internal union demands.

Testimony from May 29

The day began with the testimony of Eduardo Fachal, a worker at the factory in González Catán (a suburb of Buenos Aires). He told the court that, in a context of labor demands being rejected both by the company and the leaders of the SMATA trade union that purported to represent the workers, he and his colleagues were forced to toil under awful labor conditions. After the coup in March 1976, they were also forced to give up their demands, but they took them up again one year later because the work was unsustainable. However, after the abduction of many of their co-workers in August 1977, they finally desisted. Fachal said that to his knowledge, all the people kidnapped were involved in labor union activities. He also mentioned that Army officials were present inside the factory on various occasions and that a military post was built inside the factory where soldiers were present 24 hours a day.

Fernando Emilio Chapela was the head of personnel administration at that time. His testimony confirmed the presence of members of the Army inside the Mercedes-Benz plant. He also indicated that company executives were aware of the kidnapped workers and that the internal orders were to do nothing and keep paying their salaries to relatives.

Jorge Agustín de Marchi was detained and tortured by the Army in December 1976, in the San Justo police station. During his abduction, he shared a holding cell with three Mercedes-Benz workers, who told him that they were grassroots union delegates, that they had been in that place for months and they had been tortured.

Testimony from June 5

The hearing began with the testimony of Jorge Omar Sosa, who was kidnapped and tortured by the Army in September 1977. He was able to confirm that several Mercedes-Benz workers – delegates and activists at the factory – were in Campo de Mayo, because he saw them arrive there after being kidnapped while he was illegally detained there himself.

Worker Hugo Crosatto gave similar testimony to other former employees at the company regarding union demands being quashed and confirming that the victims in this trial participated in union activism or were members of the internal commission. He told the court about the conflict between delegates and workers, and the SMATA trade union, due to the latter’s close relationship with management. The witness Rubén Aguiar, a worker at Peugeot and a SMATA delegate, mentioned those conflicts and explained that by 1975 SMATA had stopped intervening on behalf of the workers at Mercedes-Benz.

Crosatto also provided details about the kidnapping of another worker, Juan José Martín, who was deprived of his liberty at the González Catán factory in April 1976. He emphasized that the company allowed military personnel to enter and take Martín away, and that the perpetrators of the kidnapping could not have found the place where Martín worked within the plant without help from management. He recalled that when Martín was released and returned home, he found a telegram that had been sent by Mercedes-Benz a day earlier, stating that it would grant him 15 vacation days due to his abduction. He asked himself how the company knew that he would be released the day after the telegram was sent.

Testimony from June 12

An expert witness proposed by CELS, Victoria Basualdo, explained in detail the relationship between the military and company executives, ties that dated back to other dictatorial governments. She also noted that the trade-union conflict that emerged starting in the late 1960s and that in 1975 had a key episode – which was the election of the Commission of Nine, differentiated from SMATA – contextualizes what happened starting in 1976 with the disappearance of workers from the González Catán plant. The factory went from being a place of work to being a scenario of repression; and the cycles of repressive processes were linked to moments of confrontation over labor demands. As soon as the coup took place, all the members of the Commission of Nine were summoned by the Army and threatened.

The kidnappings occurred at a time of intense labor conflict. In her research, Basualdo was able to reconstruct that Rubén Lavallén – who was in charge of company security and had already been mentioned by other witnesses – had been in charge of a clandestine detention center previously, as police commissioner of the San Justo Brigade. He was also identified by victims’ relatives as the kidnapper of Gigena and the person who tortured Martín. Lavallén died without having been tried for the crimes at Mercedes-Benz.

María Luján Ramos was married to Esteban Reimer, who remains disappeared. She told the court that company executives, after rejecting the various demands that were made, met with the internal trade-union commission on January 4, 1977 in the Libertador Avenue office and, unexpectedly, accepted all their demands. On the night of that same day, her husband was kidnapped at his home, in her presence, and he was never seen again. The only thing that the military told her, as they were leaving, was “it’s because of the factory.” Finally, she explained that, through an employee, she found out about a meeting between members of the military and Mercedes-Benz executives in which her husband’s company file was requested and provided.

José Barreiro Bueno worked at Mercedes-Benz starting in 1970, but in late 1977 he quit out of fear of being kidnapped. He was a member of the Commission of Nine and, since the start of the dictatorship, he suffered threats and persecution because of his labor activism. In his testimony, he sustained that he was not kidnapped because he had moved homes and did not advise the company. When his co-workers were being kidnapped and disappeared, the dictatorship’s forces went to find him at the home address that appeared in his company file. He also recalled that after the coup, the pressure and threats carried out by a manager named Tasselkraut intensified; at one point, the manager said “don’t worry, boys, you’ll get yours soon.” Barreiro Bueno testified that the same day Reimer and Ventura were kidnapped, the Nine had had a meeting with company executives, who suddenly decided to accept their demands.

Marcelo Barab also worked at Mercedes-Benz from 1977 to 1981. He testified about the unhealthy working conditions and the demands that were made. He said that after the kidnapping of his seven co-workers, in August 1977, other workers wanted to hold an assembly in the plant. In response, they were shot at by military officials who were inside the factory and positioned on top of Unimog trucks: “They shot at the floor to intimidate us. If not, they would have killed us all.”

Testimony from June 19

This was the last hearing in which witnesses testified. Four former Mercedes-Benz workers – Ramón Germán Segovia, José Alberto Anta, Héctor José Leiss and Aldo René Segault – gave testimony regarding the kidnapping of Héctor Ratto and Juan José Martín inside the factory, and regarding the abduction of Ventura and Reimer, members of the internal commission who were kidnapped shortly after a meeting with company executives to discuss working conditions. There was strong suspicion among the workers that the company had provided the home addresses of those kidnapped, to enable the operations. Upon entering and exiting the factory, workers were subject to searches by the security forces.

In addition, Segault gave a detailed account of the abduction of Héctor Ratto inside the González Catán plant. Military personnel in plainclothes tried to seize Ratto, but his co-workers prevented this from happening. So then armed members of the military and police went to find him and took him to the office of the manager Tasselkraut, where ultimately, after insisting that Ratto give himself up, an official document was signed that recorded the illegal detention on the pretext of a “background check”, and Ratto was taken away. A copy of this document is thought to have remained at Mercedes-Benz. Segault explained that the company allowed the security forces to enter to take Ratto away.

All the witnesses coincided in presenting a context of labor demands that went unheard, impediments to forming an internal commission in dissidence with the SMATA trade union, and the existence of a list with the names of various workers who demanded improvements. Although the segment of the Campo de Mayo mega-case involving Mercedes-Benz (in which CELS is a plaintiff) is centered on the role of six members of the military, the investigation that is still underway analyzes possible civilian responsibility in these kidnappings and disappearances. At the trial, the accused are Santiago Omar Riveros, Eugenio Guañabens Perelló, Miguel Hugo Castagno Monge, Carlos Eduardo José Somoza, Carlos Francisco Villanova and Benito Ángel Rubén Omaecheverría.

Illustration: Azul Blaseotto.