Drawing: Carlos Llerena Aguirre

The testimony of Plaintiff Eduardo Capello II demonstrated the impact of the loss of his uncle on his family and life. Mr. Capello revealed that although he was born after the death of his uncle Eduardo Capello I—his namesake—and therefore never met him, his uncle’s ghost has haunted the Capello family for five decades. After his parents were disappeared when he was young, Mr. Capello was raised by his grandparents, Jorge and Soledad, who spoke about Mr. Capello’s uncle nearly daily during his youth. Mr. Capello explained that he did not fully appreciate the pervasive fear he lived with as a child until adulthood, when he recognized that his uncle’s death—and the resulting fear of retaliation from the Argentine military and government—followed him everywhere. He testified that from a young age he knew he could not speak openly about his uncle’s death or his family’s disappearance.

According to Mr. Capello, this ever-present fear caused his family to abandon their public pursuit of justice. His grandparents filed a lawsuit in 1974 but did not feel safe pursuing the case. Ultimately fear drove the family out of Buenos Aires to the small town of Villa Gesell, 400 kilometers south. The family refused to give up, and in 2005 Mr. Capello testified that his grandmother got involved in the Argentine government’s criminal investigation into the Trelew Massacre. Mr. Capello expressed that he wanted to wait for the Argentine criminal proceedings against the other officials involved in the Trelew Massacre to unfold before turning to U.S. courts, in hopes that a conviction would lead to Mr. Bravo’s extradition. When asked what he would say to his uncle today, Mr. Capello responded: “I hope he would be just as proud of me as I was of him. It took us 50 years to get here, but we never gave up, and I’m quite sure after we conclude this proceeding the world will be just a little more just.”

Under cross-examination, Mr. Capello acknowledged that while he personally did not qualify for any benefits, his grandmother was awarded reparations from the Argentine government in the late 1990’s. Prodding as to why this lawsuit was not brought sooner, defense counsel asked Mr. Capello about his knowledge of Mr. Bravo’s location prior to the extradition attempts. Mr. Capello admitted he had performed research over the internet and learned that Mr. Bravo lived in Miami. However, he claimed he did not know Mr. Bravo’s exact address, nor contact an American lawyer or private investigator. He reported he did not understand that Mr. Bravo’s address was publicly accessible. When pressed regarding whether his fears of the Argentine government ended in the 1990’s when his family was seeking reparations, Mr. Capello responded. “No, no way, not at all.”

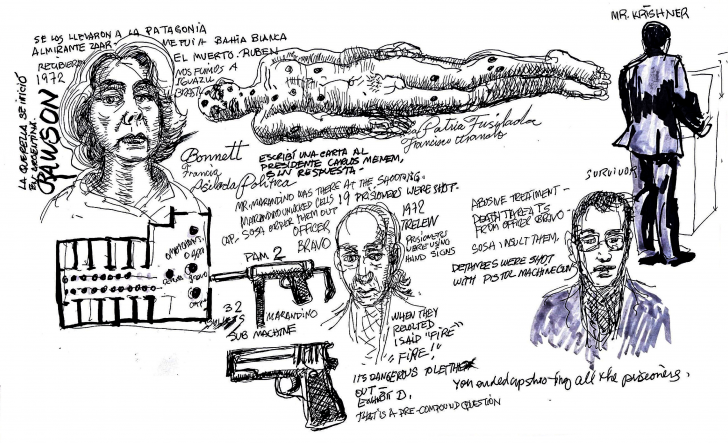

Alicia Krueger’s video deposition was played for the jury because her health prevented her from travelling to Miami. She emphasized that she would have done anything possible to pursue justice for her late first husband, Trelew Massacre victim Ruben Bonet. She explained that Mr. Bonet was arrested in 1972 without charges. She depicted the events following his arrest as a nightmare of confusion, loss, and fear. Mr. Bonet was transferred to Rawson Prison, 1500 kilometers from Buenos Aires. After the Rawson Prison escape, Ms. Krueger attempted to find Mr. Bonet to no avail. She soon learned that he was among those who succumbed to the Trelew Massacre. She viewed his body in the morgue in Pergamino. An experienced schoolteacher, Ms. Krueger brought a pencil and paper and sketched what she saw: a body riddled with bullet holes, covered in bruises, with a “head destroyed…they had put it back together.” She was able to procure autopsy reports for his body but lost them (along with all her belongings) when her family later fled their home to find safety. Many years later she found a copy of his autopsy in a book by Francisco Uronde. She lived in hiding from 1973 to 1976, at which time a military crackdown prompted her to flee the country with her family with only the clothes on their backs, taking refuge in France. She continued contacting the Argentine government, testifying that she “never stopped this struggle to seek truth and justice.” Under cross-examination, she acknowledged she twice applied for reparations and received them.

Alberto Camps’ hospital testimony after the events at Trelew was read to the jury. In it he reports that the prisoners were treated well by all the soldiers, with one exception: Lieutenant Roberto Bravo. Camps outlines the threats made by Mr. Bravo, who frequently said that rather than being fed, the prisoners should be shot. Mr. Camps writes that Mr. Bravo forced the prisoners into stress positions for over an hour. Mr. Camps explains that on the night in question, Mr. Bravo ordered the prisoners out of their cells into two lines on both sides of the hallway before giving the order to open fire. Once the gunfire began, Mr. Camps says that he dove back into his cell with his “mate” Mario Delfino. Mr. Bravo pursued them and asked if they would be more responsive to his questioning, but both men refused. Then Mr. Camps relates that Mr. Bravo fired shots at close range, killing Delfino and severely injuring Mr. Camps with a single shot to the stomach. Satisfied that the “threat” had been neutralized, Mr. Camps indicates that Mr. Bravo left the cell without calling for medical attention. Mr. Camps shares that he continued to hear rhythmic gunshots, likely from the officers’ sidearms, emanating from neighboring cells. Mr. Camps recalls that he was eventually removed from the cell and taken to the infirmary.

The day concluded with the Defendant, Mr. Bravo, taking the stand for several hours. Mr. Bravo expressed that he came to the cell block that night due to the complaints of an unnamed sailor. Feeling uncomfortable, he picked up a PAM submachine gun left by one of the corporals for security. Mr. Bravo’s fear, he said, stemmed from the earlier prison break precipitating the events at Trelew in which a guard was reportedly killed. Once the prisoners were ordered out of their cells, one of them overpowered Captain Sosa, grabbing his .45 pistol and firing two shots at the soldiers. Mr. Bravo then exclaimed: “Fire! Fire!” and emptied his magazine of its 30-32 bullets.

Certain details of Mr. Bravo’s testimony were not consistent with his prior sworn statements about the events at Trelew, including what soldiers were present, who opened the cell doors, how many shots were allegedly fired by a prisoner, and the position of each solider when the shooting commenced. Admitting to the existence of inconsistencies, Mr. Bravo testified he was trying his best to give an accurate account of events that happened 50 years ago.

Subsequently the jury was shown a document, confirmed by Mr. Bravo, illuminating his current net worth in excess of $6 Million.

Defense counsel’s questions began by focusing on Mr. Bravo’s move to the U.S. for training, something Mr. Bravo now believes was prompted by threats to his family in Argentina. Mr. Bravo reported that he made the difficult decision to stay in the U.S. for the sake of his family, and that he worked odd jobs to put himself through college and pay for his immigration lawyer. Court broke for the day around 5:00 p.m., with Mr. Bravo’s testimony scheduled to resume on Wednesday morning.